Uranium and other resources the latest threat to precious sub-arctic ecosystems

By Niels Henrik Hooge

Update: Local media source Sermitsiaq reported on January 27 that the Government of Greenland has granted the French nuclear giant Orano (former Areva) two uranium exploration permits for areas located in southwest and southeast Greenland.

The first area is 1,042 square kilometers and located north of Arsuk and Kangiinnguiet and north of Narsarsuaq. The second area is 2,485 square kilometers and consists of two sub-areas around the Ilulileq and Paatsusoq fjords and the Kangerlussuatsiaq fjord, respectively.

The governments of Greenland and Denmark are encouraging large-scale mining in Greenland, including what would be the second-largest open pit uranium mine in the world. Now groups are calling on those governments to halt such desecration and instead establish an Arctic sanctuary. Your organization can sign onto this petition. Read the petition here then send your organization name (and logo, optional) to either Niels Henrik Hooge at nielshenrik@noah.dk or to Palle Bendsen at: pnb@ydun.net.

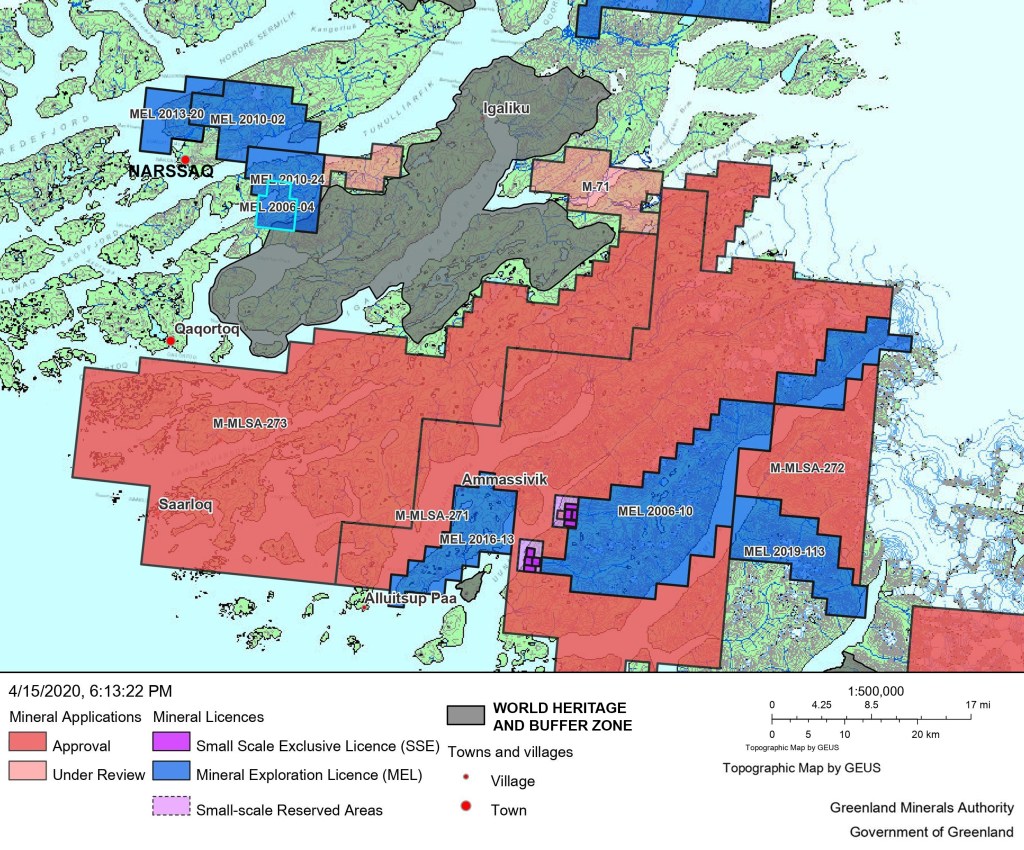

No or few World Heritage Sites probably have more or bigger mining projects in their vicinity than the Kujataa UNESCO World Heritage Site (WHS) in Southern Greenland. The property was inscribed on UNESCO’s world heritage list in 2017.

It comprises a sub-arctic farming landscape consisting of five components that represent key elements of the Norse Greenlandic and modern Inuit farming cultures.

On one hand they are distinct, on the other they are both pastoral farming cultures located on the climatic edges of viable agriculture, depending on a combination of farming, pastoralism and marine mammal hunting. The landscape constitutes the earliest introduction of farming to the Arctic.

Some of the world’s biggest mining projects are located near Kujataa

Kujaata is situated in Kommune Kujalleq, the southernmost and smallest municipality of Greenland with its rich mineral resources. These include zinc, copper, nickel, gold, diamonds and platinum group metals, but first and foremost substantial deposits of rare earth elements (REEs) and uranium.

Greenland is estimated to hold 38.5 million tons of rare earth oxides, while total reserves for the rest of the world stand at 120 million tons. Furthermore, Greenland has some of the world’s largest undiscovered oil and gas reserves and could develop into the next environmental frontline – not unlike the Amazon Rainforest in South America.

Some of the biggest REEs mining projects in the world are located only a few kilometres from the Kujataa WHS. The biggest and most controversial is the Kvanefjeld REEs-uranium mining project, owned by the Australian company Greenland Minerals Ltd., GML. According to GML, in addition to containing the second biggest uranium and by far the largest thorium deposits, the Ilimaussaq Complex, of which Kvanefjeld is a part, possesses the second largest deposits of rare earth elements in the world.

The mine, which would be the world’s second largest open pit uranium mine, is located on top of a mountain, almost one kilometre above sea-level, and only six kilometres away from Narsaq, a town of approximately 1,500 inhabitants, and also near some of the parts of the Kujataa WHS.

A second major project close to Kujataa is the Kringlerne REEs mining project, which is described by its owner, the Australian mining company Tanbreez Mining Greenland A/S, as the probably largest deposit of REEs in the world.

In 2013, the Greenlandic government estimated that Kringlerne contained more than 4.3 billion tons of ore. The minerals will be extracted from two open pits at high altitude.

A third substantial project is the Motzfeldt Sø REE mining project, which is part of the Motzfeldt Centre and owned by Tanbreez’s parent company, Rimbal Pty Ltd. So far, not much is known about this project. After years of delays, decisions on whether to grant the owners of the Kvanefjeld and Kringlerne exploitation licenses were expected to be made by the Greenlandic government later in 2020. Public hearings on the projects in the last phase of their EIA processes could start at any time.

Kvanefjeld – a contentious mining project

The plans for the Kvanefjeld mine started more than sixty years ago, not in Greenland, but in Denmark, when its uranium deposit was discovered and further explored by the Danish Nuclear Energy Commission. After the Danish rejection of nuclear power and the decision in 1988 by the Joint Committee on Mineral Resources in Greenland not to issue permits for uranium exploration and extraction, the Kvanefjeld project was off the political agenda for many years. This changed in 2008, when Kvanefjeld’s owner, GML, decided, that the company wanted to mine not only REEs, but also uranium. If it did not get permission, it would abandon the project.

From being perceived as a conspicuous example of Danish colonialism, Kvanefjeld was now marketed as a means of economic independence from Denmark.

It has since become clear though that more oil and minerals extraction is not a real prerequisite for financial autonomy. In 2014, a study was published by the University of Copenhagen and Ilisimatusarfik, the University of Greenland. It concluded that 24 concurrent large-scale mining projects would be required to zero out the financial support from Denmark.

The report also established that a mineral-based economy is not economically sustainable: when the mining industry started to recede, Greenland would find itself in the same situation as before, only with fewer resources. These findings have since been confirmed by other reports.

Calls for enlargement of the Kujataa WHS

Especially in Southern Greenland, there has long existed a notion that the Kujataa World Heritage Site in its present form has been delineated to accommodate the Kvanefjeld mining project and that the potential impacts of the other mining projects surrounding the site have not been considered.

In March 2018, responding to call for submissions by Greenland’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Church and the Danish Ministry of Culture’s Agency for Culture and Palaces, The URANI NAAMIK/NO TO URA- NIUM Society in Narsaq proposed that Kujataa should be extended to include large parts of the Erik Aappalaartup Nunaa Peninsula (or the Narsaq Peninsula), which should be entered into Greenland’s World Heritage Tentative List.

Subsequently, Narsaq Museum’s curator recommended that Landnamsgaarden and Dyrnæs Church near Narsaq should be recognised as world heritage and in a letter to URANI NAAMIK, Greenland National Museum and Archive mentioned the big Northener Farm in Narsaq as a possible world heritage prospect. Generally, the proposed sites meet a wide range of selection criteria for nomination to the World Heritage Tentative List.

Kujataa’s OUV under threat

It is also clear that Kujaata’s Outstanding Universal Value, i.e. its exceptional cultural and natural significance, will be under threat if the mining projects surrounding the site are implemented. There have already been calls to put Kujaata on the World Heritage Convention’s danger list. Kujataa’s unique farming traditions have been a determining factor in designating it as world heritage.

However, the Danish Risø National Laboratory has estimated that up to a thousand tons of radioactive dust might be released annually from just the Kvanefjeld open pit mine due to material handling, hauling and blasting and from the ore stock and waste rock piles.

Furthermore, if the tailings by some unforeseen cause such as leakages, technical problems, etc. would turn dry, massive amounts of radioactive and toxic dust would be blown away. The dust from the aforementioned sources will be carried by heavy arctic sea winds across the region, where it will affect among others agricultural activities. The predominant wind direction and the direction for the strongest winds are east- and north- eastwards, where the Kujataa WHS is located. The area, its people, domestic animals and wildlife would be chronically exposed to radioactive and other toxic species via drinking water, food and air1.

Furthermore, most if not all the planned mining projects in the area are open pit mines. Perpetual blasting with explosives on the mountain tops in the open pit mines surrounding the world heritage site and the excavation and transport by dump trucks to the mills, where the rocks are crushed, could cause considerable noise disturbance during the entire operation of the mines.

According to the EIA draft reports for the Kvanefjeld project, a dilution factor in the order of 2000 for the waste water would be required to be rendered safe for the most critical parameters. This would mean that the discharges of waste water during just one year would have to be diluted into 7 km3 of seawater in the Fiord system, which is part of the Kujataa World Heritage Site, and into 260 km3 of seawater during the planned operational lifetime of the Kvanefjeld mine.

Furthermore, seepage, leaks and spills of liquids form the tailings will cause contamination of groundwater and rivers by radioactive and non-radioactive toxic chemical species. Seafood would become contaminated as well, due to the substantial discharges of wastes into the Fiords and the coastal sea.

Large-scale mining and particularly uranium mining are incompatible with the development of three of the four sectors of the farming landscape, namely fishing and hunting, tourism and food production. It is relevant to ask how the entire character of the landscape would change in the development from a rural to an industrial area in the wake of both the big mining projects. This also pertains to the question of urban development, when among others new ports, port facilities and accommodation villages have to be built and corresponding support infrastructure implemented.

No real plans to protect Kujataa

In addition to having already ignored the threats to the Kujataa world Heritage Site, there is little indication that the Greenlandic and Danish authorities intend to protect the property in the future. It is currently governed and managed by a steering group with representatives from the Greenlandic government, the Greenland National Museum and Archives, Kujalleq Municipality, village councils, farmers, the Danish Agency for Culture and Palaces and the tourism industry.

Although it is acknowledged that the site is vulnerable, it is assumed that the buffer zones are enough to protect the integrity of the property. However, since the current management plan, which barely touches on the mining issues, was written in 2016, the number of exploration licenses in the region has exploded.

Furthermore, in its description of the impacts of the nearby mining activities, the management plan relies on a draft of an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) of the Kringlerne mining project, which was rejected by Greenland’s Environmental Agency for Mineral Resources Activities (EAMRA), because it did not contain enough relevant information.

EAMRA has also rejected the four latest EIA draft reports on the Kvanefjeld project because of lack of information. Among other things, Kvanefjeld’s owner, GML, is criticised for not providing a comprehensive assessment of the earthquake risk in the region, final results of tests of toxic elements during extraction and processing, final radiological estimates and results of investigations of impacts of radioactive minerals, and for failing to describe the alternatives regarding management of tailings and the shutdown of the tailings facility.

In September 2019, the CEO of GML was also formally reproached by Greenland’s Prime Minister and the Department of Nature and Environment’s Permanent Secretary for lobbying high-ranking civil servants and ministers who had no competence within the EIA review process in order to undermine EAMRA’s authority.

A Heritage Impact Assessment is not enough

In December 2018, the Minister of Mineral Resources and Labour was asked by a member of the Parliament whether the government would carry out a Heritage Impact Assessment (HIA) of the Kvanefjeld mining project and not make a decision on licensing the project, before it had been presented to UNESCO for an evaluation.

The Minister responded that the government would not take a position on this question before a valid exploitation application had been made by the owner of the project. This is also an issue in regard to the other big mining projects in the region, because any realistic HIA of Kujataa would need to assess the cumulative effect of the mining projects in the area.

However, it could be argued that there is already enough reason for the Greenlandic and Danish States Parties to involve UNESCO and – considering that environmental issues are at the core of the problems and Kujataa’s management plan is based on rejected EIA draft reports – to include IUCN in the process.

However, the biggest problem for not only Kujataa, but all Greenland’s three world heritage sites could be the fact that Greenland’s environmental legislation does not mandate strategic environmental impact assessments for minerals exploration areas, which means that the public is not kept informed in advance on what areas could be designated. Thus, implementation of the Aarhus Convention in Greenland should have high priority in order to reinforce Greenland’s environmental legislation.

Niels Henrik Hooge is member of NOAH Friends of the Earth Denmark’s uranium group.

Headline photo: Sunset at Narsaq by Ulannaq Ingemann for Shutterstock.

This article first appeared as chapter in the World Heritage Watch Report 2020 and is republished here with kind permission of the author and the editor.

Beyond Nuclear International

Beyond Nuclear International

Pingback: Strategic Projects under the Critical Raw Materials Act:TheSocio-Environmental Risks of Fast-Tracking Mining Projects – Dehesas Vivas

Pingback: El saqueo de Groenlandia. El uranio y otros recursos son la última amenaza | Mandala

Pingback: El saqueo de Groenlandia – El uranio y otros recursos son la última amenaza | REMA

Pingback: El saqueo de Groenlandia – El uranio y otros recursos son la última amenaza