Rhetoric of resilience

Recovery of the state or recovery of the people?

By Mia Winther-Tamaki

The Japanese people and landscapes still feel the unending impacts of a nuclear catastrophe that occurred a dozen years ago. Thousands of black bags litter the Fukushima exclusion zone enclosing radioactive earth and rubbish with nowhere to go. Japan has begun releasing millions of tons of radioactive wastewater into the sea. The death and destruction of the earthquake and tsunami — a tragedy in itself — was compounded by nuclear calamity.

On March 11, 2011, a powerful undersea earthquake unleashed the deluge that flooded the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant run by Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), causing the release of deadly nuclear radiation. Invisible and moving uncontrollably, radiation continues to contaminate soil, air, water and lives it has touched. The Japanese government was responsible for not only creating the circumstance of neglect that caused the nuclear meltdown, but also for exacerbating the impacts of nuclear fallout through a delayed and opaque response that downplayed the severity of the catastrophe.

Though the crisis was triggered by natural disasters, the nuclear catastrophe that followed was profoundly man-made. The late geographer Neil Smith describes the “unnaturalness” of disasters like Fukushima’s: “The contours of disaster and the difference between who lives and who dies is to a greater or lesser extent a social calculus.”

Following the nuclear disaster, Japan shifted to a necessary post-disaster survival and recovery strategy that can be characterized by the term “resilience,” defined by the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction as the ability to “resist, absorb, accommodate to and recover from the effects of a hazard in a timely and efficient manner, including through…preservation and restoration…” However, resilience was invoked and experienced in two distinct forms in the aftermath of Fukushima: recovery of the state and recovery of the people.

Resilience, a term originating from ecology to describe species returning to “equilibrium” after an environmental shock, has become a frequently used buzzword across many disciplines. Urban geographer Tom Slater discusses the way resilience discourse is neatly folded into neoliberal nostrums by evoking the evolutionary “naturalness” of biological processes, framing market-driven agendas as inevitably interlinked with ongoing cycles of adaptive growth.

Read MoreMilitary interests are pushing new nuclear power

The UK government has finally admitted it

By Andy Stirling and Philip Johnstone

The UK government has announced the “biggest expansion of the [nuclear] sector in 70 years.” This follows years of extraordinarily expensive support.

Why is this? Official assessments acknowledge nuclear performs poorly compared to alternatives. With renewables and storage significantly cheaper, climate goals are achieved faster, more affordably and reliably by diverse other means. The only new power station under construction is still not finished, running ten years late and many times over budget.

So again: why does this ailing technology enjoy such intense and persistent generosity?

The UK government has for a long time failed even to try to justify support for nuclear power in the kinds of detailed substantive energy terms that were once routine. The last properly rigorous energy white paper was in 2003.

Even before wind and solar costs plummeted, this recognized nuclear as “unattractive.” The delayed 2020 white paper didn’t detail any comparative nuclear and renewable costs, let alone justify why this more expensive option receives such disproportionate funding.

A document published with the latest announcement, Civil Nuclear: Roadmap to 2050, is also more about affirming official support than substantively justifying it. More significant—in this supposedly “civil” strategy—are multiple statements about addressing “civil and military nuclear ambitions” together to “identify opportunities to align the two across government.”

These pressures are acknowledged by other states with nuclear weapons, but were until now treated like a secret in the UK: civil nuclear energy maintains the skills and supply chains needed for military nuclear programs.

Read MoreNuclear roadmap is massive detour

UK plan reveals true ‘energy’ agenda is pathway to nuclear weapons sector

By Jonathon Porritt

After 14 years of Tory mismanagement, the UK finds itself bereft of an energy strategy.

This was finally confirmed in the release of the Government’s new Nuclear Roadmap. At one level, it’s just the same old, same old, the latest in a very long line of PR-driven, more or less fantastical wishlists for new nuclear in the UK. But at another, it’s a total revelation.

For years, a small group of dedicated academics and campaigners have suggested that the UK Government’s Nuclear Energy Strategy is being driven more by the UK’s continuing commitment to an “independent” nuclear weapons capability than by any authoritative energy analysis. For an equal number of years, this was aggressively rebutted by one Energy Minister after another, both Tory and Labour.

The new Nuclear Roadmap dramatically changes all that. It sets to one side any pretence that the links between our civil nuclear programme and our military defence needs were anything other than small-scale – and of no material strategic significance. With quite startling transparency and clarity, the Roadmap not only reveals the full extent of those links, but positively celebrates that co-dependency as a massive plus in our ambition to achieve a Net Zero economy by 2050.

“Startling” is actually an understatement. Such a comprehensive volte-face is rare in policy-making circles. Every effort is usually made by Ministers to obscure the scale (let along the significance) of any such screeching handbrake turns. That is so not the case with the new Roadmap.

Nobody does this work alone

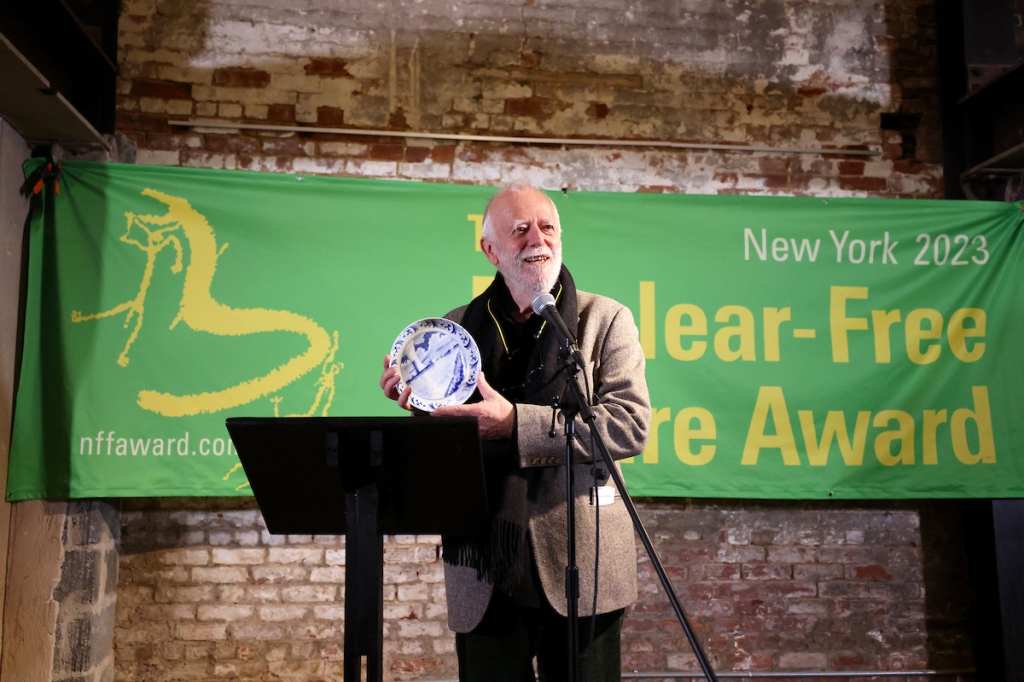

The Nuclear-Free Future Awards endeavor to ensure no-one has to

By Linda Pentz Gunter

If you are an activist in pretty much any area, you are rarely alone. The cliche, “it takes a village” applies. But it’s still possible to feel isolated and unheard, even by others in your own movement.

This is especially true for minorities and Indigenous activists, even those not necessarily working in remote areas or in countries most Westerners can’t point to on a map.

That’s why, to Claus Biegert, a founder of the Nuclear-Free Future Awards (and now a Beyond Nuclear board member), the World Uranium Hearing held in 1992 in Salzburg, Austria, was so important. Indigenous people from around the world were invited to testify about their daily experiences living with nuclear technology including uranium mining, nuclear weapons testing and radioactive waste storage.

As the people arrived, Biegert recalled, “you could see on all their faces they came from an isolated area and they felt alone and ignored.”

But at the end of the one-week conference, Biegert said, the participants left with “different faces because we helped them create a community.”

That moment gave birth in 1998 to the Nuclear-Free Future Awards, to keep that community together and to recognize the many who feel isolated and ignored, even as they do essential and often unpaid work to rid the world of nuclear dangers.

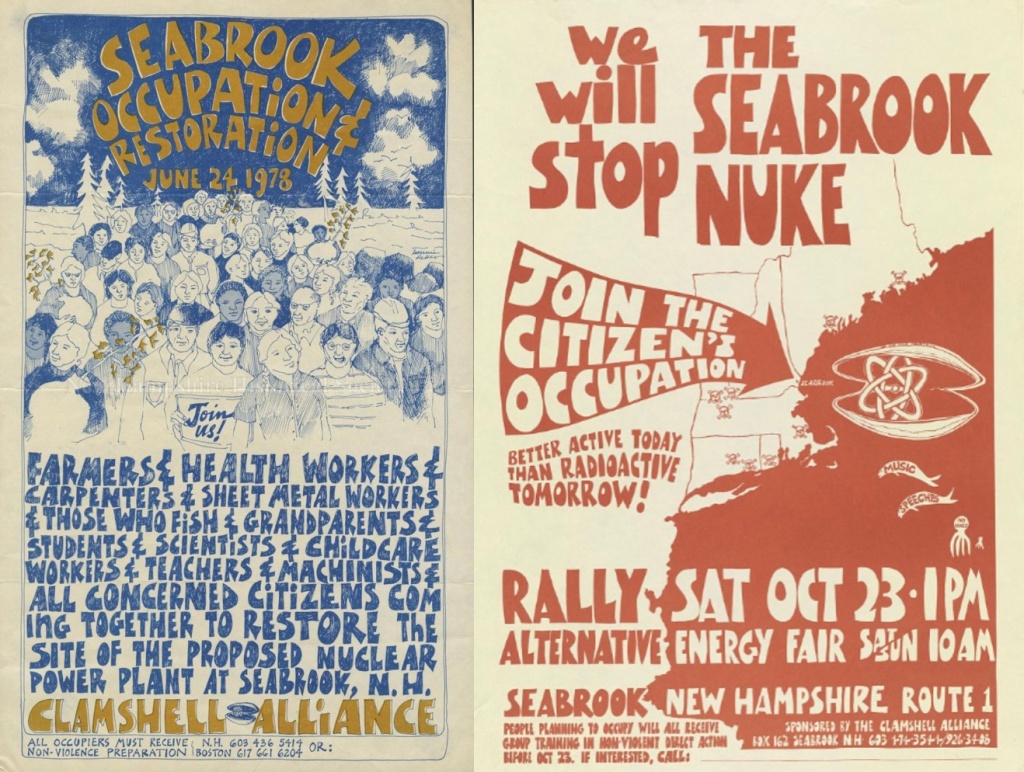

Read MoreSeasoned Clams back on the menu

Not-so-happy Clams open to new anti-nuclear challenge

By Arnie Alpert

When a nuclear reactor at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania went from a technological miracle to a pile of radioactive rubble in a matter of moments in 1979, the Portsmouth, New Hampshire office of the Clamshell Alliance became a hive of activity. I was working there at the time, fielding calls from activists and journalists from around the world. Everyone wanted our opinion since — over the previous few years — our nonviolent demonstrations to prevent the construction of the Seabrook nuclear power plant put us at the forefront of a growing social movement.

From the arrests of 18 New Hampshire residents in our first act of civil disobedience in 1976 to more than 1,400 arrests the following spring to a permitted rally that drew some 18,000 protesters in 1978, the Clamshell Alliance touched off a grassroots anti-nuclear rebellion that brought the “No Nukes” message to communities across the country and into the popular culture.

With that groundwork in place, Three Mile Island took our message to the next level. The idea that “nuclear power is a bad way to generate electricity” soon became accepted knowledge across the United States. Everyone from Wall Street tycoons to congressional staffers to ordinary voters now understood that the nuclear industry’s promise of safe, clean and affordable power was a fraud.

Unfortunately, in recent years this understanding has slowly eroded, as the industry has worked to tout its product as the answer to climate catastrophe. With the Biden administration now sinking billions into nuclear energy — and Congress on the verge of passing legislation to ease regulatory precautions on new reactors — the nuclear fraudsters are aiming for a comeback.

Read MoreTax day and war resistance

What can we learn from Philip Berrigan’s quest for peace?

By Brad Wolf

It is April 15 and we can reflect on the life and work of Philip Berrigan and undertake our own ministry of risk for peace—to ease the suffering, to restore human dignity, and to challenge our doomed policy of warmaking.

Each year Americans forfeit a sizable slice of their income to the United States Treasury to fund the government. Tax Day is dreaded. No one likes surrendering their hard-earned cash. But rather than a resigned shrug, Americans should look closely at what they are getting for their money when it comes to government services and policy.

In fiscal year 2023, the Pentagon received $858 billion for the preparation of war. This doesn’t include hidden costs for intelligence services, veterans’ benefits, Homeland Security, or the Department of Energy, which oversees the nation’s nuclear arsenal. All totaled, over $1 trillion a year is allotted for warmaking. By comparison, the 2023 budget for the U.S. Department of State, this nation’s department tasked with making peace across the globe, was a relatively miniscule $63 billion.

One way to register resistance to this profligate spending on warmaking is that of renowned peace activist and then Catholic priest Philip Berrigan. During the Vietnam War, Phil initiated the destruction of U.S. military draft files in Baltimore and Catonsville, Maryland, to save the lives of both Vietnamese and Americans, actions for which he received lengthy prison sentences.

These draft file actions by Phil initiated a new form of resistance to the Vietnam War, since no copies were kept of the draft files. Hundreds of similar actions followed at draft board offices across the country with hundreds of thousands of draft files destroyed, all stopping young men from being conscripted to kill or be killed.

Read More Beyond Nuclear International

Beyond Nuclear International