“When we squabble over trivialities, we are nothing more than useful idiots to the power elites.”

By Peter Weish

This is Peter Weish’s acceptance speech on receiving the 2018 Nuclear-Free Future Award in the category of Lifetime Achievement, on October 24 in Salzburg, Austria.

As we all know, it all began with the bomb. After the two atomic weapons of mass destruction were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the dictum shifted in the mid-1950s to “Atoms for Peace,” sparking a euphoric faith in the power of the atom. Every self-respecting country set up its own nuclear research centers and embarked on atomic energy projects.

The Austrian Atomic Energy Research Organization was founded in 1956, and in 1960 the first research reactor was built, in Seibersdorf. From 1966 to 1970, I worked at the reactor facility, in the Institute for Radiation Safety, where I noticed, with growing concern, how others were handling radioactive substances incompetently and irresponsibly yet seeking at the same time to promote these substances’ large- scale use. When the reactor’s technical director stated one day in a radio interview, “We hear constant claims that radiation causes cancer. The opposite is true – radiation cures cancer,” I had had enough.

Peter Welsh, second from left, joined fellow 2018 Nuclear-Free Future Award winners, left to right: Linda Walker, Weish, Karipbek Kuyukov, Didier and Paulette Anger. Photo: © Orla Connolly.

Together with my friend Eduard Gruber, a radio chemist, I began developing scientific arguments to counter the pro-nuclear narrative and raise public awareness. It was only much later that I chanced upon a quotation from Jean Jacques Rousseau that neatly summed up my motivation: “I would never presume to educate people if others did not seek to mislead them!” And so it was that in 1969 I published my first critical essay on nuclear energy.

Work began on the construction of a nuclear power plant near Zwentendorf in 1971. The project drew early criticism from a medical officer, Dr. Rudolf Drobil, which was published in a memorandum of the Lower Austrian Medical Association but was subsequently withdrawn following protests from officials. In those days, it was much harder than it is now to oppose blind and euphoric belief in technological progress. Early critics of nuclear power, for the most part elderly men – including a retired official formerly responsible for managing the power-grid load – faced accusations that they were in fact the very same people who had once opposed the railroads, back in the day.

Slowly and steadily, though, Austria’s planned nuclear power plants came in for increasing criticism. Several pressure groups and initiatives, organized along grassroot democratic lines, emerged, including the Austrian Opponents of Nuclear Power Plants (IÖAG) and the Vienna Organization against Nuclear Power Plants (WOGA). Strong resistance grew swiftly in Vorarlberg, where campaigners also opposed a nearby Swiss nuclear facility, just across the border. In the Waldviertel region, which was to host nuclear waste sites, there was massive resistance among the population; it was the same in Upper Austria, where a second nuclear generating facility was to be built.

March from Salzburg to Zwetendorf, 1977. Photo: Christoph Mittler.

Familiar as I was with the complex subject matter and technical terminology having co-published a scientific paperback with Edi Gruber in 1975 titled “Radioactivity and the Environment”, I was a sought-after speaker and panel member – not just in Austria but in Germany and further afield, too. As a result, I got to know many of the leading lights of the environmental and anti-nuclear movements, including Karl Bechert, Bodo Manstein, Hubert Weinzierl, Inge Schmitz-Feuerhake, Hans-Peter Dürr, Dieter Teufel, Hans-Helmut Wüstenhagen, Peter Kafka, Björn Gillberg, George Wald, John Gofman, Arthur Tamplin, Ernest Sternglass, Jinzaburo Takagi and Joanna Macy, to name but a few. Meeting people like them has been a big side benefit of being out on the road, preaching the anti-nuclear message. They and countless others have instilled in me the motivation and optimism I need to keep going.

Swayed by the many debates, rallies, large-scale demonstrations and calls for a referendum, Austria’s federal government eventually agreed to hold a plebiscite on putting the nuclear power plant into operation, though it expected it would be an easy win. The referendum was held 40 years ago, on November 5, 1978. To the surprise of many, the people of Austria actually came out against nuclear power – and this in spite of a major pro-nuclear propaganda campaign backed by millions in funding. With a turnout of more than 60%, 49.5% voted in favor and 50.5% against. The margin, though little more than 30,000 votes, was enough to ensure that the Zwentendorf nuclear power plant, although completed, never went into operation. On December 15, 1978, the Atomic Non-Proliferation Act was passed unanimously, banning nuclear power in Austria. And so it came to be that Austria switched from being one of the last industrialized countries without nuclear power to becoming the first industrialized country to eschew it.

There are important lessons to be learned from the narrow victory in that referendum: It is really important to get involved, even if the likelihood of success seems low. Every individual effort here helped to make a difference. Thousands of activists can rightfully claim for themselves that were it not for their own personal engagement, this success might never have come about. Arguably, the most important insight we gained in the anti-nuclear movement was that we could successfully overcome any ideological differences between us by working toward a common goal – much to the consternation and displeasure of the powers that be.

The Austrian people’s rejection of nuclear power – achieved through many years of discussions on energy, the environment and society – proved exemplary. The accident at Three Mile Island happened just a few months after the referendum; a few years later, there was the Chernobyl disaster; and, more recently, there was Fukushima.

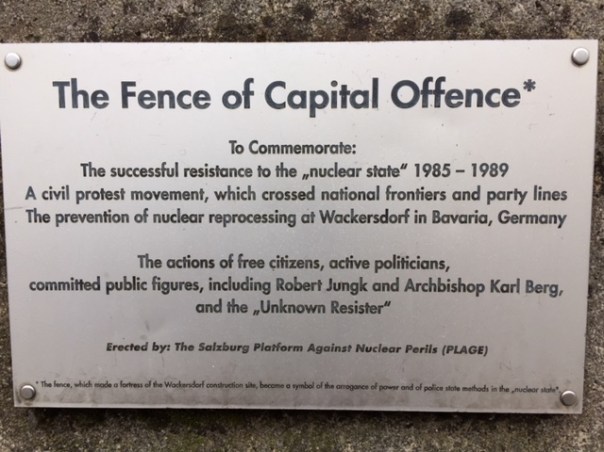

Austria is so anti-nuclear, activists in Salzburg honored their cross-boundary colleagues with a sculpture bearing this plaque. Austria has also lodged legal efforts to try to stop reactors in the UK and Hungary.

Much has changed since then, and battles have been won, but the nuclear industry is far from finished. The Hinkley Point project, for instance, exemplifies just how closely the civil and military nuclear industries remain intertwined. And the nuclear powers, rather than fulfill their obligation under Article 6 of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and continue to disarm, are playing a dangerous game by persisting in developing nuclear weapons, with the United States alone planning to spend more than a trillion dollars on its arsenal over the next ten years. The global political climate gives considerable cause for concern, and the current situation is highly volatile.

But resistance is evident, too: The United Nations adopted Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development at its high-level summit in September 2015, with all 193 member states committing to work toward implementing the Agenda’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) at the national, regional and international levels by 2030. The Agenda points emphatically to the crucial importance of peace. “There can be no sustainable development without peace,” the resolution states, “and no peace without sustainable development.” Wars are probably the most terrible thing that can happen to a society and its people, bringing suffering, death and destruction.

If you want peace, you have to understand the causes of war and violence. A glance at history reveals recurring patterns of how wars come about. They don’t occur spontaneously but are carefully planned and prepared – generally in the service of economic or geopolitical interests.

Actors pursuing these interests seek first to destabilize societies, foment discord between – and arm – different segments of the population, and set in motion a spiral of violence. They bring the established, age-old principle of “divide and conquer” to bear at various levels. The media become a mouthpiece for their pro-conflict propaganda.

They spread lies designed to stir up fear, demonize the opposition, and prepare the populace for war. They discredit and disparage moderate voices (like the so-called Putin apologists, decried today). They disguise their own agenda. They provoke their opponents into firing the first shot, or they engage in false-flag operations in order to drive their own people into the war.

They show no willingness to accept offers of peace, for they have no interest. To achieve their true objectives, they continue their murderous war of extermination until the underdog surrenders unconditionally. As victors, they get to define history and present lies and propaganda as historical fact. And they proscribe any critical assessment of events or pursuit of the real historical truth.

Theodore Roosevelt said: “Behind the ostensible government sits enthroned an invisible government owing no allegiance and acknowledging no responsibility to the people.” Photo: Rockwood Photo Co.

So it was, in the wake of 9/11, that instead of bringing the perpetrators to trial before the International Court of Justice, a so-called war on terror was waged which has since claimed many more innocent lives than the terrorism it claims to fight.

Crimes do not justify crimes. However, world politics is not driven by democratic decisions but by a powerful network – the military-industrial complex – supported by a complicit finance industry, government spy agencies, so-called think-tanks, and key elements within the mainstream media.

And this is nothing new. Theodore Roosevelt, the 26th President of the United States, said the following in 1912, three years after his presidency: “Behind the ostensible government sits enthroned an invisible government owing no allegiance and acknowledging no responsibility to the people. To destroy this invisible government, to dissolve the unholy alliance between corrupt business and corrupt politics, is the first task of the statesmanship of the day.” Overturning the power of the so-called deep state, therefore, must be the primary goal of civil society today.

To accomplish this, we must first overcome the rifts within society, because when we squabble over trivialities, we are nothing more than useful idiots to the power elites. There is another way: We can emphasize those things that we share in common rather than focus on the things that divide us; we can work together in pursuit of our common interests. And what are our key common interests? Environmental and societal problems aside, it is important that we reinforce the central importance of international law in the preservation of peace.

The United Nations Charter, an essential element of international law, bans the general use of force by states and, thus, the pursuit of wars of aggression. The task of the International Criminal Court in The Hague is to prosecute violations of this ban. However, the ICC is sabotaged by those with the most power in the world in connection with their own crimes.

And we can see that the UN Security Council, too, has obvious failings, largely on account of the veto rights held by the various nuclear powers – the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, China and France. This is a flaw that needs to be rectified in the interests of equality among nations.

Resistance to militarization of the EU, too, is a factor. In any debate surrounding our future, it is essential that we foster an objective, non-violent culture of discussion. For as the saying goes, “There is no way to peace; peace is the way.”

The treaty banning nuclear weapons passed by the UN in 2017 marks important, ground-breaking progress against the interests of the world’s nuclear powers. It has demonstrated that NGOs, together with government representatives at the international level, can build majorities against the power elites, giving us grounds for hope in the continuing battle against the nuclear threat.

Let me conclude by expressing my gratitude for this award, which I gladly accept on behalf of my fellow campaigners, many of whom have now passed away. I would like to leave you with some wise words from Albert Schweitzer which I think apply to all of us here today. When asked whether he was an optimist or a pessimist, he replied: “My knowledge is pessimistic, but my willing and hoping are optimistic.”

Peter Weish is an Austrian scientist, author and environmental activist. He played a significant part in the successful campaign to stop the Zwentendorf nuclear power plant and was honored for his role in establishing a nuclear-free Austria.

Headline photo of Peter Weish accepting the 2018 Nuclear-Free Future Lifetime Achievement Award. Photo: © Orla Connolly.

Beyond Nuclear International

Beyond Nuclear International

Pingback: Holding onto optimism in the pursuit of peace via Beyond Nuclear International –