Early reactors were primarily intended as producers of plutonium

By Linda Pentz Gunter

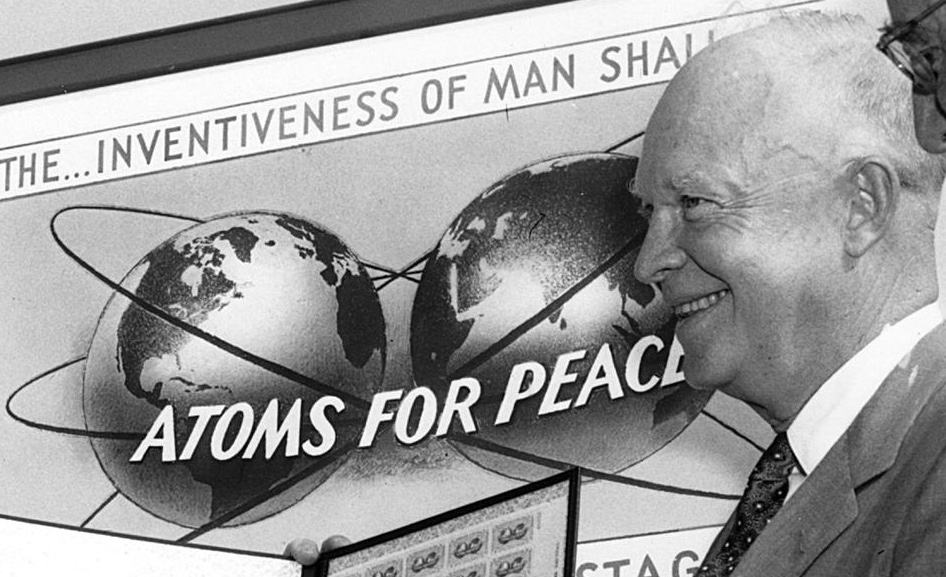

Atoms for Peace had a nice ring to it. But it was a fantasy at best, at worst, a lie. Atoms for Peace was never the intention. Atoms for war, as it turned out, was brewing in the background even before Dwight Eisenhower became president of the United States.

After summarily tossing aside the Paley Commission report delivered to his predecessor, President Truman, and which advocated the US choose the solar pathway for energy expansion, Eisenhower embraced a very different report. In 1953, the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) delivered a series of studies on Nuclear Power Reactor Technology from four groups of private industry companies.

On the cover of the report is a familiar rogues’ gallery of corporations, including Dow, Monsanto, and Bechtel.

These reports, an initiative of the companies themselves, were designed to find a way to bring private industry into the nuclear power sector. Hitherto, the nuclear sector — almost entirely focused on weapons of course — was firmly under the control of government and the military.

Whose idea was it? Says the AEC:

“Accordingly, when Dr. Charles A. Thomas, of Monsanto Chemical Co., in the summer of 1950 proposed that industry might with its own capital design, construct and operate nuclear reactors for production of plutonium and power, the AEC gave the suggestion interested consideration.”

Plutonium and power. Note which came first.

Before long there were four groups all vying to come up with the best proposal for a dual-purpose reactor — and that’s what they called them — that would make plutonium for the nuclear weapons sector, and oh yes, as a by-product, also generate electricity.

This was a stated pre-requisite, directly from the AEC. Even if Dow and Monsanto and others had wanted just to explore using nuclear power for electricity generation, the AEC required that the designs it would consider were: “not necessarily those which would have been selected had the studies been directed toward power-only reactors with the plutonium produced having but fuel value.”

They had to be dual-purpose.

And while all four groups considered dual-purpose reactors to be technically feasible, they all agreed that: “no reactor could be constructed in the very near future which would be economic on the basis of power generation alone.”

Uneconomic, then, and still today.

The four groups of companies had completed their reports in the summer of 1952. So even as the Truman government commissioned and submitted the Paley Commission to Congress — which had flagged nuclear power as having limited utility — behind the scenes, the AEC and this private industry cabal was already trying to cement in place a scheme that would legitimize nuclear power by giving it a dual-purpose, the more important one being its role in further building up the US nuclear weapons arsenal.

This determination, to tie civil and military nuclear reactor technology together; to say that reactor technology should serve primarily to produce plutonium; effectively gave nuclear power an immovable seat at the energy table.

And all of this eclipsed and supplanted renewable energy development, despite what the Paley Commission had recommended, because of course renewable energy had no utility to the military sector.

None of the reactors presented by the four groups in the AEC report was ever built. In fact, no commercial, civilian-owned reactors were ever built in the United States that adopted the dual power production and plutonium production concept.

Instead, the US was already opening the way for private industry to develop, own and operate commercial nuclear power plants for the purpose of generating electricity. This effectively obviated the need to pursue the dual-purpose reactor path.

If the Paley Commission path had been taken, and the US had decided to lead the world in solar energy, we might not have had climate change at all.

Instead, we got Atoms for Peace and nuclear power retained its seat at the nuclear weapons table. Not because it was the most economical, most abundant and most sustainable choice for energy production. It was none of these. But because of that special caché —it’s connection to nuclear weapons.

Despite the national pride at the time about Atoms for Peace, it was a fatal step in the wrong direction, miring the country in vast costs and an enormous inventory of radioactive waste.

The connection between nuclear power and nuclear weapons remains unbroken, cemented in place by the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), specifically, by Article IV which reads:

“Nothing in this Treaty shall be interpreted as affecting the inalienable right of all the Parties to the Treaty to develop research, production and use of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes.”

Unfortunately, these words were lifted verbatim and inserted into the otherwise excellent Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

Article IV of the NPT even encourages the development of nuclear power in “non-nuclear-weapon States Party to the Treaty, with due consideration for the needs of the developing areas of the world.”

So, when a non-nuclear weapons country signs the Treaty, thereby declaring it will not develop nuclear weapons, its reward is not only permission, but encouragement to develop nuclear power, regardless of that country’s energy needs, climate, demographics, topography or political volatility.

Thus, you have a country like Saudi Arabia — along with others in the now ever more volatile Middle Eastern region — eager to develop nuclear power. Saudi Arabia’s argument is that this will allow it to export more oil rather than burn it, thus reducing its carbon emissions. All good for climate change, it says.

But if Saudi Arabia really needs a home-grown energy source, why would it embark on a long, slow and expensive program of building nuclear power plants? Surely a sunny and windy place like Saudi Arabia would be developing solar and wind power if this was really about electricity needs?

It’s quite obvious why Saudi Arabia wants nuclear power. It at least opens the option for a pathway to nuclear weapons, and it sends a message to its enemies in that region — most notably Iran — about that capacity to do so.

Allowing for the “inalienable right” to nuclear energy leaves the drawbridge to the peace castle perpetually down, an open invitation to marauders to charge in bearing the means to develop nuclear weapons. What began as a bad idea in 1953 should not be enshrined in laws meant to make the world nuclear-free.

This essay was derived from a January 31, 2021 talk given by the author at the Beyond Nuclear conference hosted by Helensburgh, Scotland Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. Linda Pentz Gunter is the international specialist at Beyond Nuclear and writes for and curates Beyond Nuclear International.

Heading photo of nuclear waste protests — the inevitable product of nuclear power use — by Rio Werner Hauser/Creative Commons.

Beyond Nuclear International

Beyond Nuclear International

Pingback: Atoms for Peace was never the plan via Beyond Nuclear International | The Atomic Age

Pingback: Atoms for Peace was never the plan « nuclear-news

Pingback: Atoms for Peace was never the plan « Antinuclear

Pingback: Nuclear news – week to 31st October « nuclear-news

Pingback: Nuclear news – week to 31st October « Antinuclear