Reflections from an 87-year journey

Every Winter Solstice, Walt Patterson, a UK-based Canadian physicist and widely published writer and campaigner on energy, sends Solstice Greetings to some 600 friends and colleagues around the world. Beyond Nuclear was one of the recipients. It’s a delightful read to start the new year, with some important reflections, so we republish it here, thereby expanding Walt’s circle of “friends and colleagues.”

By Walt Patterson

Once more the time rolls round to send you the traditional Solstice Greetings. I am frankly dumfounded to realize that since I arrived on this planet the earth has gone the whole way around the sun eighty-seven times. A lot has happened to me in those eighty-seven trips, and I’m delighted to find that I can still recall a lot of it, despite the stroke that hit me two years ago. Was that really only two years ago? Amazing.

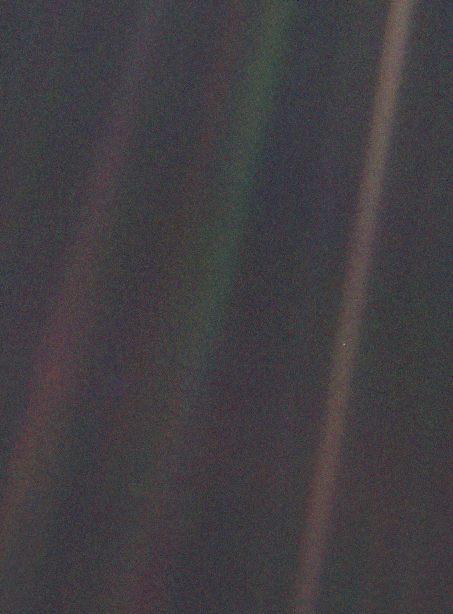

In 1990 the NASA Voyager spacecraft 3.7 billion miles away took and sent back to us the photo that Carl Sagan the US astronomer called ‘The pale blue dot’. For what we call eighty-seven years, I’ve been riding this pale blue dot around the universe, as it circles an unremarkable ordinary star in a tenuous arm of what we call our local galaxy. Even on the blue dot I’ve covered a lot of ground.

Soon after I got here, Otto Frisch, Otto Hahn and Lise Meitner discovered nuclear fission in uranium. Physics had long been the most dramatic and exciting branch of science, but now nuclear physics leapt to the forefront. My first love of science was astronomy, but as an impressionable youngster I decided I wanted to study nuclear physics too. I did, acquiring a post-graduate Master’s degree, and was about to try for a PhD at the University of Edinburgh, until I changed my mind.

After leaving my home town of Winnipeg in the middle of Canada, five hundred miles from anywhere, I had spent the winter in Greenwich Village in Manhattan, crossed the Atlantic on a freighter, travelled around the UK in an old black London taxicab with two South African guys and three Australian girls, hitchhiked all over northern Europe, including an unforgettable ride with a fellow Danish hitchhiker in a vast American convertible with two young US GIs who picked us up at the Dutch-German border and drove us all the way to Copenhagen.

When I reached Wien (Vienna) on my return trip I walked to the Zentralfriedhof, the Central Cemetery, which is far from central as it proved, and found area 31, the burial place of great composers. I can’t now recall which exactly were actually buried there rather than just memorials; walking among the statues of many Strausses, and Mozart and Schubert and Beethoven and Bach, the air and my head were filled with melody, a vivid sensation.

In due course I reached Paris, and explored the riverside bookstalls along the Seine, where I was delighted to find many titles I knew were banned not only in Canada but also in the US and the UK, notably Tropic of Cancer by Henry Miller and other Miller books, which I duly bought and devoured, smuggled into the UK, where with my expatriate Canadian mates I held endless boozy pub bull-sessions discussing Miller and Lawrence Durrell, from whom I’m sure I acquired a fascination with Greece.

When improbably the opportunity arose I made my way to Greece, to a remote island found by odd circumstances, where in due course the brilliant and lovely woman who became my life-mate, my late beloved Cleone joined me. Having abandoned my stated plans to gain a PhD, I had always enjoyed writing, and harbored vague thoughts of becoming a writer, and by early 1968 I at last completed what I still think of as my statutory unpublished first novel. I typed it laboriously on my battered Royal portable with six carbon copies, and sent carbons to my erstwhile Canadian pub-chat mates.

To my astonishment one of these mates, an extraordinary fellow ex-Winipegger called Bob Hunter, inspired by my novel effort, abruptly materialized to visit me at my new home with Cleone in the Bucks countryside. Now a columnist with the Vancouver Sun, Bob during his visit told us about a ferment boiling up on the west coast of North America about something called ‘the environment’. To Cleone and me this was an apocalypse, a revelation that changed our lives.

As we gradually became ‘environmentalists’, reading Barry Commoner and Paul Ehrlich, I also grew aware of a controversy involving nuclear physics, about what was called ‘nuclear power’, a topic on which I had no prior knowledge; but I spoke the language.

This narrow-angle color image of the Earth, dubbed ‘Pale Blue Dot’, is a part of the first ever ‘portrait’ of the solar system taken by Voyager 1. From Voyager’s great distance Earth is a mere point of light, less than the size of a picture element even in the narrow-angle camera. Coincidentally, Earth lies right in the center of one of the scattered light rays resulting from taking the image so close to the sun. This blown-up image of the Earth was taken through three color filters – violet, blue and green – and recombined to produce the color image. The background features in the image are artifacts resulting from the magnification. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Poets, including the future poet laureate Ted Hughes, founded a small magazine called Your Environment. By accident I learned about it, got in touch and found out they wanted to write about radioactive waste. I offered to do a piece for them; they accepted, and I set to work to learn about radioactive waste. I then wrote an article which I entitled ‘Odorless, Tasteless and Dangerous’. Your Environment published it, and I was hooked. I began working unpaid for the little magazine, and attending press conferences about environmental issues, while I read everything I could about them. I also wrote book reviews, yet more info about environment issues.

I was not impressed by a lurid screed called ‘ Perils of the Peacful Atom’, but the low-key prose of ‘The Careless Atom’ by Sheldon Novick was much more convincing. I contacted Novick, then editing a US magazine just called ‘Environment‘, and offered him a piece on ‘The British Atom’ about UK nuclear power. He accepted and I set to work gathering info.

After it appeared, I found myself learning and writing, and indeed speaking, about nuclear power and its problems. At one point, to my gratification, Penguin Books invited me to write for them a book about nuclear power. Luckily for me they also set me up with Gerry Leach as an editor; with his invaluable help I produced a text that became a Pelican book entitled Nuclear Power, that eventually sold some 130,000 copies in English, and appeared in five other languages.

Alas, as I reminisced about where I’ve been riding on the blue dot I found myself writing a memoir — a good idea, but not for Solstice Greetings. When I get to it, it will include Stockholm June 1972, Washington DC, San Francisco, Rome, Hong Kong, Vancouver, New Zealand, Australia, Germany, Hiroshima, France, Toronto, Seoul, and many other places at various points on the Earth’s orbit.

Eighty-seven years after I got here the blue dot is now in serious trouble. Not the dot itself, but all of us creatures riding on it. My eighty-seven year ride coincides precisely with the time we have been living with the knowledge about nuclear fission. As I have contemplated it most of my life I have been compelled to conclude that nuclear electricity, so-called nuclear power, has never been a normal economic activity, it has never paid its way, and still does not, it has always relied on vast injections of money and resources from taxpayers and electricity users, decreed by governments.

Civil nuclear power has been in effect a cover story, to disguise the true reason for pouring so much of our wealth into this dangerous sinkhole. In the eyes of governments, the key nuclear activity has been to stockpile terrifying quantities of nuclear explosives for use as weapons, nuclear political power, in which someone says, in effect, unless you do what I want, or give me what I want, I’ll obliterate this blue dot.

As climate change makes more and more of the blue dot uninhabitable, conflicts are breaking out world-wide. We have to hope that some people, some of our fellow dot-riders, some states-people, can find a way to defuse the nuclear threat.

Best wishes for a better 2024 — Walt.

Since 1991 Walt Patterson has been a Fellow of what is now the Energy, Environment and Resources Programme at Chatham House in London. He is a Fellow of the Energy Institute, London, and a Visiting Fellow of the Science Policy Research Unit at the University of Sussex. He is chair of the Seoul International Energy Advisory Council and a founder-member of the International Energy Advisory Council

Headline photo: Updated version of “Pale Blue Dot” by NASA/Wikimedia Commons.

The opinions expressed in articles by outside contributors and published on the Beyond Nuclear International website, are their own, and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of Beyond Nuclear. However, we try to offer a broad variety of viewpoints and perspectives as part of our mission “to educate and activate the public about the connections between nuclear power and nuclear weapons and the need to abandon both to safeguard our future”.

Beyond Nuclear International

Beyond Nuclear International

Pingback: “Civil nuclear power” has always been a cover story for wasting public money on nuclear weapons. « nuclear-news