A $36.8 billion lesson from Georgia

Ratepayers beware. New nuclear power plants will gouge customers

From Georgia Conservation Voters Education Fund and Georgia WAND

Georgia consumer groups have filed a major lawsuit against the State of Georgia [AF1] in federal court, alleging Georgia lawmakers violated the state’s constitution by unilaterally postponing Georgia Public Service Commission (PSC) elections. According to the lawsuit, the PSC election’s unlawful postponement allowed the sitting commission members to rubberstamp the largest utility rate increases in Georgia history and grant utility companies the authority to charge Georgians for cost-overruns and mishaps. The groups argue that the charges may not have been passed onto consumers if elections were held as regularly scheduled.

House Bill 1312, which Georgia legislators passed in April, delays the election of new PSC members until at least 2025, giving multiple sitting PSC members an extra two years in office. Georgia’s constitution requires that PSC terms shall be six years, and therefore cannot be lengthened without a constitutional amendment. All PSC members have had their office terms extended to eight years, and one nine years as a result.

The lawsuit, filed by Georgia based attorneys Bryan Sells and Lester Tate on behalf of plaintiffs Georgia WAND and Georgia Conservation Voters, follows the U.S. Supreme Court’s denial of the plaintiffs’ petition for the court to review the 11th Circuit’s decision in Rose v Raffensperger.

Kimberly Scott, plaintiff and executive director of Georgia WAND, said: “The illegal postponement of PSC elections in Georgia is an attack on our constitutional right to vote and the state’s constitutional mandate to hold statewide elections within the time frame governed by the law. This lawsuit will show that Georgia lawmakers have made de facto regulatory decisions that are harmful to the state instead of adhering to our constitution. Let the people vote!”

Read MoreAgreement is proliferation nightmare

Australia arms up with UK and US help

The following is a statement to be delivered on July 23 at the 2024 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Preparatory Committee event in Geneva by Jemila Rushton, Acting Director, International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, Australia. It was endorsed by a number of groups, including Beyond Nuclear. It has been adapted slightly for style as a written piece rather than oral delivery.

By Jemila Rushton

We gather in uncertain and dangerous times. All nine nuclear armed states are investing in modernizing their arsenals, none are winding back policies for their use. The number of available deployed nuclear weapons is increasing. We do not have the luxuries of time or inaction.

Against this background where the proliferation of nuclear weapons is an ongoing concern, Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States of America continue to further develop AUKUS, an expanded trilateral security partnership between these three governments.

AUKUS has two pillars. Pillar One was first announced in September 2021 and relates to information, training and technologies being shared by the US and UK to Australia to deliver eight nuclear powered submarines to Australia. Vessels which, if they eventuate, will utilize significant quantities of highly enriched uranium (HEU). It also allows Australia to purchase existing US nuclear submarines. Currently, Australia is committing billions of dollars to both US and UK submarine industry facilities as part of the AUKUS agreement, potentially enabling the further development of nuclear armed capability in these programs.

Two years ago, during the 2022 NPT Review Conference, many governments expressed concern that the AUKUS nuclear submarine deal would undermine the NPT, increase regional tensions, lead to proliferation, and threaten nuclear accidents in the ocean. There remains an urgent need to critique the nuclear proliferation risks posed by AUKUS.

The Australian decision to enter into agreements around nuclear powered submarines was made on the assumption that it would be permitted to divert nuclear material for a non-prescribed military purpose, by utilizing Paragraph 14 of the International Atomic Agency’s (IAEA) Comprehensive Safeguards Agreement (CSA). The ‘loophole’ of Paragraph 14 potentially allows non-nuclear armed states to acquire nuclear material, which would be removed from IAEA safeguards.

Read MoreBiden signs ADVANCE Act. Now what?

Congress wants to “accelerate” new reactor build, putting public safety in jeopardy

By Dave Kraft/NEIS

On Wednesday July 10th President Joe Biden signed the “ADVANCE Act,” which stands for “Accelerating Deployment of Versatile, Advanced Nuclear for Clean Energy.”

The controversial bill aggressively promotes the narrow, short-term interests of the U.S. nuclear industry in ways that threaten the long-term national environmental, climate and national/international security interests.

Further, it functionally rewrites the mandate of the federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) in ways that potentially cast it into the role of promoter instead of federal regulator of the controversial and moribund nuclear power industry.

To summarize, The ADVANCE Act:

- promotes development of currently experimental, commercially non-existent “small modular nuclear reactors” (SMNRs) and allegedly “advanced” reactors, using tax dollars;

- provides less regulatory oversight by ordering the NRC to “streamline” licensing of currently experimental SMNRs, putting the NRC in a position of becoming a quasi-promoter instead of regulator, in contradiction to its 1975 founding mandate;

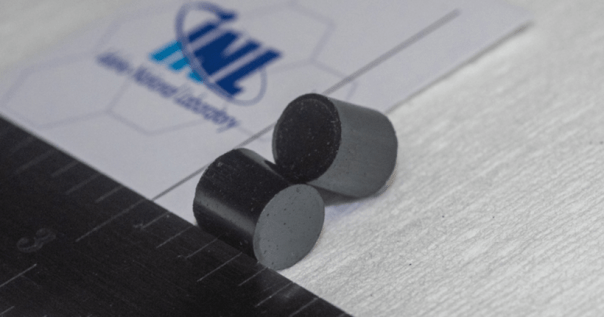

- requires development of the infrastructure needed to produce more intensely enriched radioactive fuel called “HALEU” – high-assay, low-enriched uranium — required for the SMNRs to run on. Enrichment would be just below weapons-usable; currently the only source of HALEU is Russia;

- ignores the potential increased risk and harm from having more nuclear reactors large and small;

- produces more high-level radioactive waste without first having a disposal method in place for either current or future reactors;

- permits and encourages export of nuclear technology and materials internationally; and

- for the first time, allows foreign control/ownership of nuclear facilities within the U.S.

The overblown hype of the nuclear “bros”

The pro-nuclear bros are intent on selling us small modular reactors, but their happy talk is rooted in misinformation, writes Ed Lyman

Even casual followers of energy and climate issues have probably heard about the alleged wonders of small modular nuclear reactors, or SMRs. This is due in no small part to the “nuclear bros”: an active and seemingly tireless group of nuclear power advocates who dominate social media discussions on energy by promoting SMRs and other “advanced” nuclear technologies as the only real solution for the climate crisis. But as I showed in my 2013 and 2021 reports, the hype surrounding SMRs is way overblown, and my conclusions remain valid today.

Unfortunately, much of this SMR happy talk is rooted in misinformation, which always brings me back to the same question: If the nuclear bros have such a great SMR story to tell, why do they have to exaggerate so much?

What Are SMRs?

SMRs are nuclear reactors that are “small” (defined as 300 megawatts of electrical power or less), can be largely assembled in a centralized facility, and would be installed in a modular fashion at power generation sites. Some proposed SMRs are so tiny (20 megawatts or less) that they are called “micro” reactors. SMRs are distinct from today’s conventional nuclear plants, which are typically around 1,000 megawatts and were largely custom-built. Some SMR designs, such as NuScale, are modified versions of operating water-cooled reactors, while others are radically different designs that use coolants other than water, such as liquid sodium, helium gas, or even molten salts.

To date, however, theoretical interest in SMRs has not translated into many actual reactor orders. The only SMR currently under construction is in China. And in the United States, only one company—TerraPower, founded by Microsoft’s Bill Gates—has applied to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) for a permit to build a power reactor (but at 345 megawatts, it technically isn’t even an SMR).

The nuclear industry has pinned its hopes on SMRs primarily because some recent large reactor projects, including Vogtle units 3 and 4 in the state of Georgia, have taken far longer to build and cost far more than originally projected. The failure of these projects to come in on time and under budget undermines arguments that modern nuclear power plants can overcome the problems that have plagued the nuclear industry in the past.

Regulators are loosening safety and security requirements for SMRs in ways which could cancel out any safety benefits from passive features.

Developers in the industry and the U.S. Department of Energy say that SMRs can be less costly and quicker to build than large reactors and that their modular nature makes it easier to balance power supply and demand. They also argue that reactors in a variety of sizes would be useful for a range of applications beyond grid-scale electrical power, including providing process heat to industrial plants and power to data centers, cryptocurrency mining operations, petrochemical production, and even electrical vehicle charging stations.

Here are five facts about SMRs that the nuclear industry and the “nuclear bros” who push its message don’t want you, the public, to know.

1. SMRs Are Not More Economical Than Large Reactors

In theory, small reactors should have lower capital costs and construction times than large reactors of similar design so that utilities (or other users) can get financing more cheaply and deploy them more flexibly. But that doesn’t mean small reactors will be more economical than large ones. In fact, the opposite usually will be true. What matters more when comparing the economics of different power sources is the cost to produce a kilowatt-hour of electricity, and that depends on the capital cost per kilowatt of generating capacity, as well as the costs of operations, maintenance, fuel, and other factors.

According to the economies of scale principle, smaller reactors will in general produce more expensive electricity than larger ones. For example, the now-cancelled project by NuScale to build a 460-megawatt, 6-unit SMR in Idaho was estimated to cost over $20,000 per kilowatt, which is greater than the actual cost of the Vogtle large reactor project of over $15,000 per kilowatt. This cost penalty can be offset only by radical changes in the way reactors are designed, built, and operated.

For example, SMR developers claim they can slash capital cost per kilowatt by achieving efficiency through the mass production of identical units in factories. However, studies find that such cost reductions typically would not exceed about 30%. In addition, dozens of units would have to be produced before manufacturers could learn how to make their processes more efficient and achieve those capital cost reductions, meaning that the first reactors of a given design will be unavoidably expensive and will require large government or ratepayer subsidies to get built. Getting past this obstacle has proven to be one of the main impediments to SMR deployment.

The levelized cost of electricity for the now-cancelled NuScale project was estimated at around $119 per megawatt-hour (without federal subsidies), whereas land-based wind and utility-scale solar now cost below $40/MWh.

Another way that SMR developers try to reduce capital cost is by reducing or eliminating many of the safety features required for operating reactors that provide multiple layers of protection, such as a robust, reinforced concrete containment structure, motor-driven emergency pumps, and rigorous quality assurance standards for backup safety equipment such as power supplies. But these changes so far haven’t had much of an impact on the overall cost—just look at NuScale.

In addition to capital cost, operation and maintenance (O&M) costs will also have to be significantly reduced to improve the competitiveness of SMRs. However, some operating expenses, such as the security needed to protect against terrorist attacks, would not normally be sensitive to reactor size. The relative contribution of O&M and fuel costs to the price per megawatt-hour varies a lot among designs and project details, but could be 50% or more, depending on factors such as interest rates that influence the total capital cost.

Economies of scale considerations have already led some SMR vendors, such as NuScale and Holtec, to roughly double module sizes from their original designs. The Oklo, Inc. Aurora microreactor has increased from 1.5 MW to 15 MW and may even go to 50 MW. And the General Electric-Hitachi BWRX-300 and Westinghouse AP300 are both starting out at the upper limit of what is considered an SMR.

Overall, these changes might be sufficient to make some SMRs cost-competitive with large reactors, but they would still have a long way to go to compete with renewable technologies. The levelized cost of electricity for the now-cancelled NuScale project was estimated at around $119 per megawatt-hour (without federal subsidies), whereas land-based wind and utility-scale solar now cost below $40/MWh.

Microreactors, however, are likely to remain expensive under any realistic scenario, with projected levelized electricity costs two to three times that of larger SMRs.

2. SMRs Are Not Generally Safer or More Secure Than Large Light-Water Reactors

Because of their size, you might think that small nuclear reactors pose lower risks to public health and the environment than large reactors. After all, the amount of radioactive material in the core and available to be released in an accident is smaller. And smaller reactors produce heat at lower rates than large reactors, which could make them easier to cool during an accident, perhaps even by passive means—that is, without the need for electrically powered coolant pumps or operator actions.

However, the so-called passive safety features that SMR proponents like to cite may not always work, especially during extreme events such as large earthquakes, major flooding, or wildfires that can degrade the environmental conditions under which they are designed to operate. And in some cases, passive features can actually make accidents worse: For example, the NRC’s review of the NuScale design revealed that passive emergency systems could deplete cooling water of boron, which is needed to keep the reactor safely shut down after an accident.

In any event, regulators are loosening safety and security requirements for SMRs in ways which could cancel out any safety benefits from passive features. For example, the NRC has approved rules and procedures in recent years that provide regulatory pathways for exempting new reactors, including SMRs, from many of the protective measures that it requires for operating plants, such as a physical containment structure, an offsite emergency evacuation plan, and an exclusion zone that separates the plant from densely populated areas. It is also considering further changes that could allow SMRs to reduce the numbers of armed security personnel to protect them from terrorist attacks and highly trained operators to run them. Reducing security at SMRs is particularly worrisome, because even the safest reactors could effectively become dangerous radiological weapons if they are sabotaged by skilled attackers. Even passive safety mechanisms could be deliberately disabled.

Considering the cumulative impact of all these changes, SMRs could be as—or even more— dangerous than large reactors. For example, if a containment structure at a large reactor reliably prevented 90% of the radioactive material from being released from the core of the reactor during a meltdown, then a reactor five times smaller without such a containment structure could conceivably release more radioactive material into the environment, even though the total amount of material in the core would be smaller. And if the SMR were located closer to populated areas with no offsite emergency planning, more people could be exposed to dangerously high levels of radiation.

But even if one could show that the overall safety risk of a small reactor was lower than that of a large reactor, that still wouldn’t automatically imply the overall risk per unit of electricity that it generates is lower, since smaller plants generate less electricity. If an accident caused a 250-megawatt SMR to release only 25% of the radioactive material that a 1,000-megawatt plant would release, the ratio of risk to benefit would be the same. And a site with four such reactors could have four times the annual risk of a single unit, or an even greater risk if an accident at one reactor were to damage the others, as happened during the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi accident in Japan.

3. SMRs Will Not Reduce the Problem of What to Do With Radioactive Waste

The industry makes highly misleading claims that certain SMRs will reduce the intractable problem of long-lived radioactive waste management by generating less waste, or even by “recycling” their own wastes or those generated by other reactors.

First, it’s necessary to define what “less” waste really means. In terms of the quantity of highly radioactive isotopes that result when atomic nuclei are fissioned and release energy, small reactors will produce just as much as large reactors per unit of heat generated. (Non-light-water reactors that more efficiently convert heat to electricity than light-water reactors will produce somewhat smaller quantities of fission products per unit of electricity generated—perhaps 10 to 30%—but this is a relatively small effect in the scheme of things.) And for reactors with denser fuels, the volume and mass of the spent fuel generated may be smaller, but the concentration of fission products in the spent fuel, and the heat generated by the decay products—factors that really matter to safety—will be proportionately greater.

Therefore, entities that hope to acquire SMRs, like data centers that lack the necessary waste infrastructure, will have to safely manage the storage of significant quantities of spent nuclear fuel on site for the long term, just like any other nuclear power plant does. Claims by vendors such as Westinghouse that they will take away the reactors after the fuel is no longer usable are simply not credible, as there are no realistic prospects for licensing centralized sites where the used reactors could be taken for the foreseeable future. Any community with an SMR will have to plan to be a de facto long-term nuclear waste disposal site.

4. SMRs Cannot Be Counted on to Provide Reliable and Resilient Off-the-Grid Power for Facilities, Such as Data Centers, Bitcoin Mining, Hydrogen, or Petrochemical production

Despite the claims of developers, it is very unlikely that any reasonably foreseeable SMR design would be able to safely operate without reliable access to electricity from the grid to power coolant pumps and other vital safety systems. Just like today’s nuclear plants, SMRs will be vulnerable to extreme weather events or other disasters that could cause a loss of offsite power and force them to shut down. In such situations a user such as a data center operator would have to provide backup power, likely from diesel generators, for both the data center AND the reactor. And since there is virtually no experience with operating SMRs worldwide, it is highly doubtful that the novel designs being pitched now would be highly reliable right out of the box and require little monitoring and maintenance.

It very likely will take decades of operating experience for any new reactor design to achieve the level of reliability characteristic of the operating light-water reactor fleet. Premature deployment based on unrealistic performance expectations could prove extremely costly for any company that wants to experiment with SMRs.

5. SMRs Do Not Use Fuel More Efficiently Than Large Reactors

Some advocates misleadingly claim that SMRs are more efficient than large ones because they use less fuel. In terms of the amount of heat generated, the amount of uranium fuel that must undergo nuclear fission is the same whether a reactor is large or small. And although reactors that use coolants other than water typically operate at higher temperatures, which can increase the efficiency of conversion of heat to electricity, this is not a big enough effect to outweigh other factors that decrease efficiency of fuel use.

Some SMRs designs require a type of uranium fuel called “high-assay low enriched uranium (HALEU),” which contains higher concentrations of the isotope uranium-235 than conventional light-water reactor fuel. Although this reduces the total mass of fuel the reactor needs, that doesn’t mean it uses less uranium nor results in less waste from “front-end” mining and milling activities: In fact, the opposite is more likely to be true.

If the nuclear bros have such a great SMR story to tell, why do they have to exaggerate so much?

One reason for this is that HALEU production requires a relatively large amount of natural uranium to be fed into the enrichment process that increases the uranium-235 concentration. For example, the TerraPower Natrium reactor which would use HALEU enriched to around 19% uranium-235, will require 2.5 to 3 times as much natural uranium to produce a kilowatt-hour of electricity than a light-water reactor. Smaller reactors, such as the 15-megawatt Oklo Aurora, are even more inefficient. Improving the efficiency of these reactors can occur only with significant advances in fuel performance, which could take decades of development to achieve.

Reactors that use uranium inefficiently have disproportionate impacts on the environment from polluting uranium mining and processing activities. They also are less effective in mitigating carbon emissions, because uranium mining and milling are relatively carbon-intensive activities compared to other parts of the uranium fuel cycle.

SMRs may have a role to play in our energy future, but only if they are sufficiently safe and secure. For that to happen, it is essential to have a realistic understanding of their costs and risks. By painting an overly rosy picture of these technologies with often misleading information, the nuclear bros are distracting attention from the need to confront the many challenges that must be resolved to make SMRs a reality—and ultimately doing a disservice to their cause.

Ed Lyman is director of Nuclear Power Safety at the Union for Concerned Scientists. This article was first published by Common Dreams and is republished under a Creative Commons license.

Headline photo: Bill Gates (right, pictured with Rick Perry) is one of the biggest nuclear bros of all. (Photo: DOE/Wikimedia Commons)

The opinions expressed in articles by outside contributors and published on the Beyond Nuclear International website, are their own, and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of Beyond Nuclear. However, we try to offer a broad variety of viewpoints and perspectives as part of our mission “to educate and activate the public about the connections between nuclear power and nuclear weapons and the need to abandon both to safeguard our future”.

A vigil behind bars

Pair who protested US nuclear bombs in Germany serving time

By Susan Crane and Susan van der Hijden

Here in Rohrbach prison we are awakened by the sounds of doves and other birds, giving the illusion that all is well in the world, until other sounds, keys rattling, doors being shut, and guards doing the morning body check, bring us back to reality.

We are sitting in a prison cell, 123 km from Büchel Air Force Base, where more than 20 U.S. nuclear bombs are deployed.

At the moment, the runway at Büchel is being rebuilt to accommodate the new F-35 fighter jets that will carry the new B61-12 nuclear bombs that were designed and built in the U.S.

The planning, preparation, possession, deployment, threat or use of these B61-bombs is illegal and criminal. The U.S., Germany and NATO know that each B61 nuclear bomb would inflict unnecessary suffering and casualties on combatants and civilians and induce cancers, keloid growth and leukemia in large numbers, inflict congenital deformities in unborn children and poison food supplies.

“We have no right to obey,” says Hannah Arendt.

Although our actions might seem futile, we understand that it is our right, duty and responsibility to stand against the planning and preparation for the use of these weapons. They are illegal under the Non-Proliferation Treaty, which both Germany and the U.S. have signed and ratified, and under the the Hague Convention, the Geneva Convention and the Nuremberg Charter.

Read MoreWhy ‘no’ to NATO?

Alliance spreads nuclear weapons, nuclear energy and risk, writes David Swanson

Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty declares that NATO members will assist another member if attacked by “taking action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force.” But the UN Charter does not say anywhere that warmaking is authorized for whoever jumps in on the appropriate side.

The North Atlantic Treaty’s authors may have been aware that they were on dubious legal ground because they went on twice to claim otherwise, first adding the words “Any such armed attack and all measures taken as a result thereof shall immediately be reported to the Security Council. Such measures shall be terminated when the Security Council has taken the measures necessary to restore and maintain international peace and security.” But shouldn’t the United Nations be the one to decide when it has taken necessary measures and when it has not?

The North Atlantic Treaty adds a second bit of sham obsequiousness with the words “This Treaty does not affect, and shall not be interpreted as affecting in any way the rights and obligations under the Charter of the Parties which are members of the United Nations, or the primary responsibility of the Security Council for the maintenance of international peace and security.” So the treaty that created NATO seeks to obscure the fact that it is, indeed, authorizing warmaking outside of the United Nations — as has now played out in Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, and Libya.

While the UN Charter itself replaced the blanket ban on all warmaking that had existed in the Kellogg-Briand Pact with a porous ban plagued by loopholes imagined to apply far more than they actually do — in particular that of “defensive” war — it is NATO that creates, in violation of the UN Charter, the idea of numerous nations going to war together of their own initiative and by prior agreement to all join in any other member’s war. Because NATO has numerous members, as does also your typical street gang, there is a tendency to imagine NATO not as an illegal enterprise but rather as just the reverse, as a legitimizer and sanctioner of warmaking.

Read More Beyond Nuclear International

Beyond Nuclear International