Jaitapur: A risky and expensive project for India

Six-reactor EPR project moves forward with cost and safety issues unresolved

By Suvrat Raju and M.V. Ramana

In December, the French company Électricité de France (EDF) submitted a “techno-commercial proposal” to the Indian government for the Jaitapur nuclear power project in Maharashtra. The idea of importing six nuclear European Pressurised Reactors (EPRs) was initiated by the United Progressive Alliance government more than a decade ago, but the project had made little progress due to concerns about the economics and safety of the EPRs, local opposition, and the collapse of the initial French corporate partner, Areva. Despite these problems, in the past few months, the Modi government has taken several high-level steps towards actuating the project.

In March 2018, EDF and the Nuclear Power Corporation of India (NPCIL) signed an “industrial way forward” agreement in the presence of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and French President Emmanuel Macron. Last month, after meeting the French Foreign Minister, Jean-Yves Le Drian, External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj announced that “both countries are working to start the Jaitapur project as soon as possible”. The urgency is inexplicable as it comes before the techno-commercial offer has been examined and as earlier questions about costs and safety remain unanswered. Moreover, with the Indian power sector facing surplus capacity and a crisis of non-performing assets (NPAs), a large investment in the Jaitapur project is particularly risky.

Black Mist, Burnt Country

Artists respond to the devastation of British atomic tests at Maralinga

By Linda Pentz Gunter

During the Cold War, more than two thousand atomic tests were carried out by the nuclear weapons powers. They chose to detonate some of these “tests” over the heads of unwilling, and mainly unwitting people, who, having been exposed to the radioactive fallout, were then callously treated as guinea-pigs.

One of the least-known chapters in this disgraceful history is the part played by Great Britain, which tested its atomic bombs in Australia. The tests there took place in the 1950s. There were 12 detonations, mainly at Maralinga and also Emu Field and Monte Bello Islands.

Revelations in a recent book, Maralinga, by Frank Walker showed how British scientists secretly used the affected Australian population to study the long-term effects of radiation exposure, much like the Americans did with Marshall Islanders. Although the scientists involved began by testing animal bones, they soon moved on to humans. A directive was issued by UK scientists to “Bring me the bones of Australian babies, the more the better,” an experimentation that lasted 21 years.

Road to Maralinga II by Karen Standke (b. 1973)

We need a green planet at peace

The new US Congress should make a New Peace Deal

By Medea Benjamin and Alice Slater

(Opinions of op-ed writers on these pages are their own)

A deafening chorus of negative grumbling from the left, right, and center of the US political spectrum in response to Trump’s decision to remove US troops from Syria and halve their numbers in Afghanistan appears to have slowed down his attempt to bring our forces home. However, in this new year, demilitarizing US foreign policy should be among the top items on the agenda of the new Congress. Just as we are witnessing a rising movement for a visionary Green New Deal, so, too, the time has come for a New Peace Deal that repudiates endless war and the threat of nuclear war which, along with catastrophic climate change, poses an existential threat to our planet.

We must capitalize and act on the opportunity presented by the abrupt departure of “mad dog” Mattis and other warrior hawks. Another move toward demilitarization is the unprecedented Congressional challenge to Trump’s support for the Saudi-led war in Yemen. And while the president’s disturbing proposals to walk out of established nuclear arms control treaties represents a new danger, they are also an opportunity.

Khalid (6) walks next to a burnt up car outside of his home in Sana’a, Yemen after an airstrike. (Photo: Becky Bakr Abdulla/NRC/Irin)

Can the Green New Deal be saved?

A brave new climate plan challenged establishment Democrats to act; they balked

There is a new crop of progressives in the House of Representatives. Democratic Congresswoman, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, other mainly women freshmen colleagues, and a new youth movement (see video below), have taken the lead on pushing for the Green New Deal, an energy plan that addresses the urgency of climate change and calls for the elimination of all fossil fuels and nuclear energy.

But when Ocasio-Cortez offered a resolution for the establishment of a House select committee to explore the Green New Deal, it was promptly and predictably killed by the Democratic leadership who instead established their own Select Committee. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi has tapped Florida Congresswoman, Kathy Castor to chair it. The panel will not directly address crafting a Green New Deal proposal.

However, the youth-led non-partisan Sunrise Movement, says the Green New Deal is far from dead. Group members have been actively recruiting support for the Green New Deal on Capitol Hill — they currently have 45 Members of Congress on board and counting. They gained headlines during Congressional sit-ins (which Ocasio-Corez joined) and arrests (see video below). They view Pelosi’s decision as nothing more than a corporate-backed copout and vow to fight on, organizing around the country to build support and momentum.

Poisoned water and deadly dust

Navajo community contaminated by uranium suffers loss of loved ones and livestock

By Anna Benally

My name is Anna Benally and I am a member of the Navajo Tribe. I am a resident of Redwater Pond Road Community and have lived here all my life. My clan is Redhouse and Yellow Meadow people. I am currently a registered voter with Coyote Canyon Chapter House.

I remember at a very young age when mining came into our community. It was the United Nuclear Corporation (UNC) and Kerr-McGee companies that moved operations in about one mile from where I resided. The two mines were about a half mile from each other. The mine operation was a 24/7 operation in my backyard for about ten to fifteen years of my life.

Anna Benally

During this time, my mother, Mildred Benally, was a homemaker, rug weaver and had livestock, sheep, goats, horses and cattle. My father, Tom Benally, was a Medicine Man which was handed down from his dad. This was also the same for his brother, Frank Benally, my uncle. He was married to Marita Benally, a sister to my mother Mildred. They all lived at the Black Tree Standing area. Tom was also a member of the Grazing Committee for the Coyote Canyon Chapter House for 8 years. After that he started working for UNC as a laborer. This included repairing lamps and cleaning dressing rooms for workers.

During my childhood days, my siblings and I were instructed to herd sheep. It was a priority to make sure that the livestock were well taken care of, especially watering them daily. Raising livestock was our way of life and that was the way we understood the importance of respecting them and treating them as members of the family. Having livestock made us feel complete so it was important to take care of them. In addition, we also used some of our sheep as a source of food for traditional ceremonials and other family gatherings.

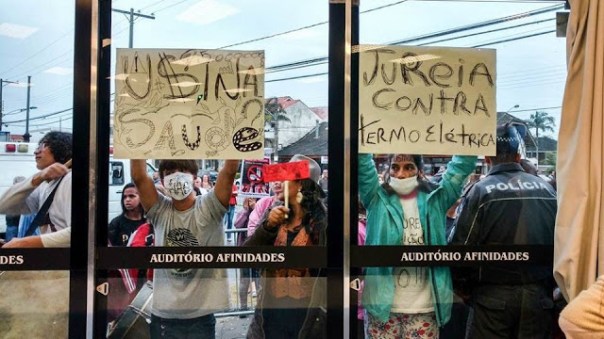

“We do not accept anything that harms our mother Earth”

The people of Peruíbe joined together for a renewable energy future

By Linda Pentz Gunter

Sometimes we win. We join together and we fight for what’s right and we prevail. We do it in the name of a nuclear-free world. Or we do it for climate change, or for peace. These victories are important. They deserve to be celebrated and shared and talked about. And they can serve as models for others, guides, roadmaps to success. Inspiration. As we head into a new year we need all of this.

Every time we fight off a uranium mine, a pipeline, a fossil fuel or nuclear plant, an incinerator or nuclear waste dump, we do it for Mother Earth, our only home. While some want to contemplate — and spend billions on — the possibility of living on inhospitable alternative planets like Mars, the rest of us know that if we don’t protect the precious planet we already have, we are pretty much doomed.

Indigenous people have a lot to teach the rest of us about sustainable stewardship of the land, respect for animals and the protection of our precious resources. Over the centuries, the rest of us haven’t been very good at listening, We have preferred to massacre, dominate, impose servitude. We have bombed, and mined, drilled and destroyed.

We coined words like “savages” to describe fellow human beings whose respect for life on Earth is anything but. It is we who have been savage. And remain so. We still aren’t listening. The Dakota Access Pipeline got approved. Nuclear waste could be buried under Beatrix Potter’s Lake District. Rainforests continue to be burned and clear cut.

Young people were prominent in the movement to stop a massive natural gas project in Peruíbe

Beyond Nuclear International

Beyond Nuclear International