A crisis at Kursk?

The Russian war against Ukraine now threatens to envelop one of its own nuclear power plants, writes Linda Pentz Gunter

The trouble with nuclear technology, of any kind really, is that it depends on sensible and even intelligent decisions being made by supremely fallible human beings. The consequences of even a simple mistake are, as we have already seen with Chornobyl, catastrophic.

To add to the danger, nuclear technology also relies on other seemingly elusive human traits, beginning with sanity but also something that ought to be — but all too often isn’t —fundamentally human: empathy. That means not wanting to do anything to other people you wouldn’t want to endure yourself. But of course we see humans doing these things every day, whether at the macro individual level or on a geopolitical scale. We just have to look at events in Congo, Gaza, Haiti, Sudan; the list goes on.

And of course we cannot ignore what is playing out in Ukraine and now Russia. Because of the war there, dragging on since Russia’s February 24, 2022 invasion of Ukraine, we remain in a perpetual state of looming nuclear disaster.

Currently, the prospects of such a disaster are focused on Russia, where that country’s massive Kursk nuclear power plant is the latest such facility to find itself literally in the line of fire as Ukrainian troops make their incursion there in response to Russia’s ongoing war in their country.

But we cannot forget the six-reactor site at Zaporizhzhia in Ukraine either, embroiled in some of the worst fighting in that country, the plant occupied by Russian troops for more than two years and also perpetually one errant missile away from catastrophe.

Read MoreWhy the big push for nuclear power as “green”?

Heavy lobbying by France and a “military romance” provide some answers, write Andy Stirling and Phil Johnstone

Whatever one’s view of nuclear issues, an open mind is crucial. Massive vested interests and noisy media clamour require efforts to view a bigger picture. A case in point arises around the European Commission’s much criticised proposal – and the European Parliament’s strongly opposed decision – to last year accredit nuclear power as a ‘green’ energy source In a series of legal challenges, the European Commission and NGOs including Greenpeace are tussling over what kind and level of ’sustainability’ nuclear power might be held to offer.

To understand how an earlier more sceptical EC position on nuclear was overturned, deeper questions are needed about a broader context. Recent moves in Brussels follow years of wrangling. Journalists reported intense lobbying – especially by the EU’s only nuclear-armed nation: France. At stake is whether inclusion of nuclear power in the controversial ‘green taxonomy’ will open the door to major financial support for ‘sustainable’ nuclear power.

Notions of sustainability were (like climate concerns) pioneered in environmentalism long before being picked up in mainstream policy. And – even when its comparative disadvantages were less evident – criticism of nuclear was always central to green activism. So, it might be understood why current efforts from outside environmentalism to rehabilitate nuclear as ‘sustainable’ are open to accusations of ‘greenwash’ and ‘doublespeak’.

In deciding such questions, the internationally-agreed ‘Sustainable Development Goals’ are a key guide. These address various issues associated with all energy options – including costs and wellbeing, health effects, accident risks, pollution and wastes, landscape impacts and disarmament issues. So, do such comparative pros and cons of nuclear power warrant classification alongside wind, solar and efficiency?

On some aspects, the picture is relatively open. All energy investments yield employment and development benefits, largely in proportion to funding. On all sides, simply counting jobs or cash flowing through favoured options and forgetting alternatives leads to circular arguments. If (despite being highlighted in the Ukraine War), unique vulnerabilities of nuclear power to attack are set aside, then the otherwise largely ‘domestic’ nature of both nuclear and renewables can be claimed to be comparable.

Read MoreHumanity on a knife’s edge

Trump took us to the nuclear brink. What happens if he’s back?

By Lawrence S. Wittner

Over the past decade and more, nuclear war has grown increasingly likely. Most nuclear arms control and disarmament agreements of the past have been discarded by the nuclear powers or will expire soon. Moreover, there are no nuclear arms control negotiations underway. Instead, all nine nuclear nations (Russia, the United States, China, Britain, France, India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea) have begun a new nuclear arms race, qualitatively improving the 12,121 nuclear weapons in existence or building new, much faster, and deadlier ones.

Furthermore, the cautious, diplomatic statements about international relations that characterized an earlier era have given way to public threats of nuclear war, issued by top officials in Russia, the United States, and North Korea.

This June, UN Secretary-General António Guterres warned that, given the heightened risk of nuclear annihilation, “humanity is on a knife’s edge.”

This menacing situation owes a great deal to Donald Trump.

As President of the United States, Trump sabotaged key nuclear arms control agreements of the past and the future. He single-handedly destroyed the INF Treaty, the Iran nuclear agreement, and the Open Skies Treaty by withdrawing the United States from them. In addition, as the expiration date for the New START Treaty approached in February 2021, he refused to accept a simple extension of the agreement—action quickly countermanded by the incoming Biden administration.

Read MoreThe Trump link to Ohio nuke corruption

Former president’s top campaign money bundler connected to Ohio’s largest public corruption scandal

By David DeWitt, Ohio Capital Journal

FirstEnergy was the company behind the largest political bailout and bribery scandal in Ohio history, which funneled $61 million in dark money bribes to Ohio lawmakers in order to pass a $1.3 billion nuclear and coal bailout at the expense of every Ohio family that pays utility bills.

Now, Sludge has reported that Donald Trump’s top known campaign money bundler advised FirstEnergy on its contributions to a dark money group that pleaded guilty to racketeering charges in Ohio’s House Bill 6 bailout scandal.

FirstEnergy pleaded guilty in a deferred prosecution agreement. So did the aforementioned dark money group used to funnel the bribes, Generation Now. Former Republican Ohio House Speaker Larry Householder is serving 20 years in federal prison on racketeering charges, and former Ohio Republican Party chair and FirstEnergy lobbyist Matt Borges is serving five years for his role.

One former Ohio lobbyist charged in the scandal died by suicide, as did Ohio’s former top utility regulatorwhile he was under state and federal indictments. FirstEnergy admitted bribing him $4.3 million. Two other former FirstEnergy lobbyists cooperated and are awaiting sentencing. Two former FirstEnergy executives have been charged by the state of Ohio on charges alleging the spearheaded the bribery scheme. They’ve pleaded not guilty.

Trump’s top money bundler is named Geoff Verhoff. As Sludge reported, Verhoff is a “senior adviser at public affairs firm Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld, has bundled more than $3.6 million this year for Trump 47 Committee, according to a new filing with the Federal Election Commission.”

Read More79 years since the unthinkable

But are we closer than ever to nuclear war?

By Kate Hudson

As we mourn the loss of all those killed at Hiroshima and Nagasaki by US atomic bombs, in August 1945, we cannot avoid the fact that we are closer than ever to nuclear war. The war on Ukraine is greatly increasing the risk. So too is NATO’s location of upgraded nuclear weapons across Europe — including Britain — and Russia’s siting of similar weapons in Belarus. Irresponsible talk suggesting that “tactical” nuclear weapons could be deployed on the battlefield — as if radiation can be constrained in a small area — makes nuclear use more likely.

And our own government is leading the charge on greater militarisation and is in denial about the dangers it is unleashing. This is a bad time for humanity — and for all forms of life on Earth. It’s time for us to stand up and say No: we refuse to be taken into nuclear Armageddon.

Help in raising awareness of the existential peril of nuclear weapons is coming from an unusual quarter — Hollywood. Many of us have seen the blockbuster, Oppenheimer. Many in the movement have their criticisms but my own feeling is that you cannot leave the film without being aware of the terror of nuclear weapons, and their world-destroying capacity.

I attended a screening hosted by London Region CND; it was sold out within hours, and followed by a dynamic audience discussion that lasted till 11pm. I recognised only two people in the audience. That’s the crowd we need to engage with — none of us just want to preach to the converted. But there is a particular flaw in the film I must raise, as we remember Hiroshima Day.

It was repeatedly suggested that dropping the bomb was necessary to end the second world war. Although there was eventually a quick aside that countered this, it could easily have been missed. So for the record, this is the reality of what happened.

Read MoreThe pictures worth a thousand words

Canada’s little-known role in atomic bombings on display

By Anton Wagner

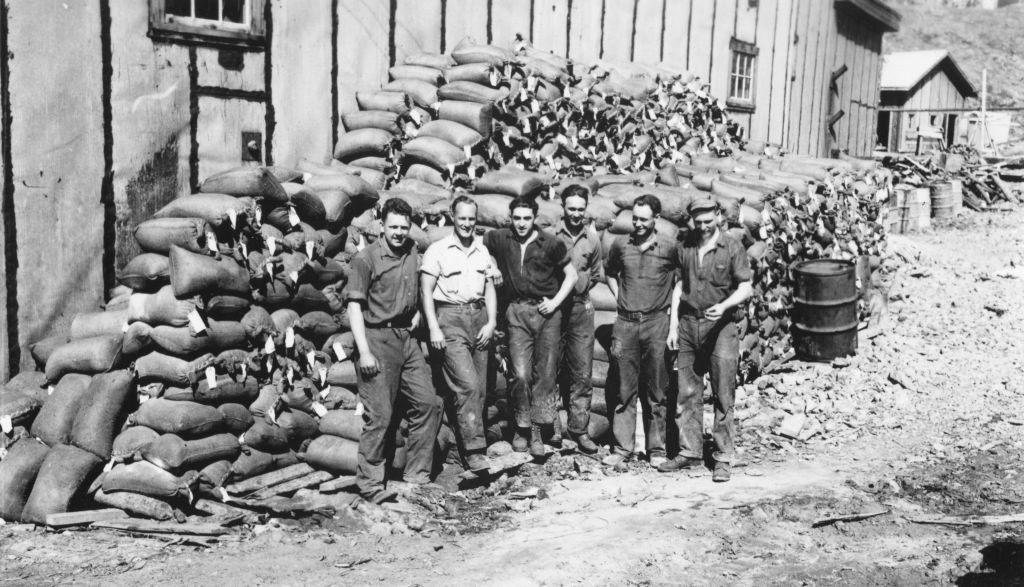

The Hiroshima Nagasaki Day Coalition launched a “Canada and the Atom Bomb” photo exhibition inside Toronto City Hall on August 2. The exhibition of 100 photographs reveals the Canadian government’s participation in the American Manhattan Project that developed the atom bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945.

The exhibition can be viewed in its entirety online at the Toronto Metropolitan University website.

It documents how the Eldorado Mining and Refining Company extracted uranium ore at Great Bear Lake in the Northwest Territories in the late 1930s and shipped the ore to its refinery in Port Hope, Ontario, for sale to the Americans.

Images by the Montreal photographer Robert Del Tredici focus on the Dene hunters and trappers at Great Bear Lake who were hired by Eldorado to carry the sacks of radioactive ore on their backs for loading onto barges that transported the ore to Port Hope. Many of them subsequently died of cancer.

Read More Beyond Nuclear International

Beyond Nuclear International