A farce that would make Feydeau blush

France still trying to sell its reactors despite nuclear fiasco at home

By Linda Pentz Gunter

I’ve been searching for the equivalent word in French for ‘chutzpah’ but so far ‘insolence’ or ‘audace’ just doesn’t quite cover President Emmanuel Macron’s renewed pitch to sell French nuclear technology to the United States.

Nevertheless, that was a central purpose of Macron’s state visit to the nation’s capital last week. In a mise-en-scène worthy of a Feydeau farce, he even brought a whole atomic entourage with him including representatives from the state regulator (Autorité de sûreté nucléaire) as well as cabinet members and the (bankrupt) French nuclear power industry.

It’s chutzpah because the backdrop to Macron’s nuclear promotional tour is the most breathtaking pile of wreckage imaginable. Sacre bleu! If you wanted to paint a picture of a complete industrial fiasco, you need only look at today’s French nuclear power industry.

And yet, here is Macron still blithely attempting to sell the French “flagship” reactor, the EPR, likely second only to the breeder reactor as the most abject failure in nuclear power plant history. EPR stands for Evolutionary Power Reactor. With it, France has achieved the unimaginable, to send evolution in reverse.

Macron has not abandoned the beloved breeder either, which also managed to reverse the legend of its namesake — Phénix — by descending metaphorically into the ashes of nuclear history. And oulàlà, a similar fate befell the Superphénix, a bigger breeder and an even bigger fiasco that cost $10.5 billion and produced power only sporadically before it was permanently shuttered.

French Green Party politician, Dominique Voynet, called Superphénix “a stupid financial waste,” which accurately describes any and all of today’s new nuclear power aspirations.

And yet, last February, just before the elections that saw him retain his throne in the presidential palace, Macron announced the country would go full (radioactive) steam ahead. France would build between 6 and 14 new EPR-2 reactors (yes, the “new improved” EPR!) in the name of climate, extend the operating licenses of the entire current reactor fleet, initiate projects for small modular reactors, and resume exploration of so-called Generation IV (read “fast” or “breeder”) reactors.

Macron bragged that France would build six of the new reactors on three existing sites, with the first start-up date around 2035 and at an estimated cost of $52 billion.

Whatever Macron’s smoking, they’re not Gauloises.

Read More‘Guinea Pig Nation’

NRC will weaken regulations for new “advanced” reactors says scientist

By Karl Grossman

“Guinea Pig Nation: How the NRC’s new licensing rules could turn communities into test beds for risky, experimental nuclear plants,” is what physicist Dr. Edwin Lyman, Director of Nuclear Power Safety with the Union of Concerned Scientists, titled his presentation last week.

The talk was about how the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission is involved in a major change of its “rules” and “guidance” to reduce government regulations for what the nuclear industry calls “advanced” nuclear power plants.

Already, Lyman said, at a “Night with the Experts” online session organized by the Nuclear Energy Information Service, the NRC has moved to allow nuclear power plants to be built in thickly populated areas. This “change in policy” was approved in a vote by NRC commissioners in July.

For a more than a half-century, the NRC and its predecessor agency, the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, sought to have nuclear power plants sited in areas of “low population density”—because of the threat of a major nuclear plant accident.

But, said Lyman, who specializes in nuclear power safety, nuclear proliferation and nuclear terrorism, the NRC in a decision titled “Population-Related Siting Considerations for Advanced Reactors,” substantially altered this policy.

The lone NRC vote against the change came from Commissioner Jeffery Baran who in casting his ‘no’ vote wrote “Multiple, independent layers of protection against potential radiological exposure are necessary because we do not have perfect knowledge of new reactor technologies and their unique potential accident scenarios….Unlike light-water reactors, new advanced reactor designs do not have decades of operating experience; in many cases, the new designs have never been built or operated before.”

He noted a NRC “criteria” document which declared that the agency “has a longstanding policy of siting nuclear reactors away from densely populated centers and preferring areas of low population density.”

But, said Baran, under the new policy, a “reactor could be sited within a town of 25,000 people and right next to a large city. For reactor designs that have not been deployed before and do not have operating experience, that approach may be insufficiently protective of public health and safety…And it would not maintain the key defense-in-depth principle of having prudent siting limitations regardless of the features of a particular reactor design—a principle that has been a bedrock of nuclear safety.”

That is just one of the many reductions proposed in safety standards.

Read MoreNo use in the climate crisis

New Talking Points delivers all the reasons why small modular reactors have no role to play for climate change

By Linda Pentz Gunter

We’ve written a lot on these pages about small modular reactors (including again last week) and there’s a reason. Even though SMRs are a mirage, languishing as aspirational power point reactors loaded with false promises, there is a tsunami of license applications coming down for them.

And we are saddled with a compliant Congress, White House and nuclear regulator, all of whom have bought into the Great Lie that SMRs can do something — anything — for the climate crisis. So they will likely rubber stamp the lot. Unless we stop them.

On December 2 it will be 80 years since the first human-made self-sustaining chain reaction occurred, at the Chicago Pile-1 under the leadership of Enrico Fermi and his team. That generated the first cupful of radioactive waste, which, along with the numerous other attendant problems of nuclear energy, has never been solved. Here we are, 80 years later, still relentlessly tilting at nuclear windmills. By now, we ought to know better.

You would think it would be obvious to anyone giving this technology a second thought, that given the immense lead times, high costs, uncertainties about design and safety, and the complete absence of a radioactive waste management plan, any nuclear reactor, large or small, is a climate liability, not a solution.

Nevertheless, the empirical evidence is being drowned out by denial. “We don’t get to net zero by 2050 without nuclear power in the mix,” US Special Climate Envoy, John Kerry, unhelpfully, and untruthfully, told a press conference during the COP27 climate summit while announcing SMR deals with Romania and Ukraine.

It’s possible that our illustrious leaders know better. They just prefer to maintain the creature comforts of the status quo, content to be the puppets of big polluters — fossil fuels and nuclear power — where the votes and, more importantly, the money are.

We can’t compete with the money. But we can change the votes. Elected officials want to stay elected. That means pleasing their electorate. So they need to hear from us. Because when it comes to pushing small modular reactors, we aren’t at all pleased.

Read MoreIn the grip of the energy crisis

How has the Russian war impacted Germany’s renewable revolution?

By Sören Amelang, Clean Energy Wire

The energy crisis fueled by Russia’s war against Ukraine is dealing a heavy blow to Europe’s biggest economy Germany, due to its large dependence on Russian fossil fuels. Policymakers, businesses and households alike are struggling to cope with skyrocketing prices, which are fanning fears of irreparable damages to the country’s prized industries, economic hardships for its citizens, and social unrest. The long-term impact on the country’s landmark energy transition remains uncertain, as Germany redoubles efforts to roll out renewables, but also bets on liquefied natural gas (LNG), a temporary revival of coal plants and a limited runtime extension for its remaining nuclear plants to weather the storm. This article provides an overview of the state of play of Germany’s shift to climate neutrality, which is now dominated by its response to the crisis. It will be updated regularly. [UPDATE: Government earmarks 83 billion euros for gas and power price subsidies.]

What’s the energy crisis’ impact on the economy and households?

- The energy crisis is set to push Germany into a recession, as rising energy prices put a damper on industrial production and inflation means citizens will buy less. Both the government and the country’s leading economic research institutes expect the economy to shrink in 2023. The government forecasts an inflation rate of 8 percent in 2022, and 7 percent in 2023.

- Many German industrial companies have relied on cheap Russian pipeline gas, among them key producers of basic materials needed for many other products. These firms are particularly concerned about the energy crisis, as permanently higher gas prices threaten competitiveness and long-term survival.

- The government has launched massive relief packages for citizens and companies (see below). Without these, many households would face additional energy costs running into thousands of euros per year, with retail gas prices multiplying for many citizens, and retail power prices also rising steeply.

- Policymakers, consumer protection groups, and social care services have warned that the energy price hike could result in social hardships and even unrest if households are overburdened. But so far, protests have remained limited in scope and scale, and mainly limited to regions notorious for their rejection of government policies.

- Most citizens blame the energy price hike on external factors such as the pandemic and the war on Ukraine, and generally approve of the government’s handling of the crisis, according to surveys. They also say that they are ready to contribute to energy savings. But rising prices have become the biggest concern for a vast majority of the population.

Holtec loses its bid to reopen Palisades

Cracked and dangerous reactor should be ‘autopsied’ as part of decommissioning

By Linda Pentz Gunter

Sometimes good things happen. Or at least the right thing. Sometimes we win one.

Last May, Entergy Corporation, the owner of the Palisades single unit nuclear power plant in Covert, Michigan, announced it was closing the reactor for good. This was a huge relief because Palisades was — and is —arguably the most dangerously degraded reactor in the United States.

At 51, the Palisades reactor was having more than a mid-life crisis. It was in possession of the most embrittled reactor pressure vessel in the country; it had a severely degraded reactor lid; and its steam generators were worn out — all key safety components.

As my Beyond Nuclear colleague, Kevin Kamps, who’s from Michigan said, “we are thankful that this reactor has indeed been shut down before it melted down.”

But there was a wrinkle. The reactor was sold to Holtec, a notorious US company with a spotty track record, which has been buying up reactors in order to decommission them. It has already faced a number of accusations over its decommissioning procedures at the closed Oyster Creek reactor site in New Jersey.

However, when the Biden administration started dangling $6 billion in funding via the Civil Nuclear Credit program in front of struggling reactor owners — in an effort to keep nuclear power plants running —Holtec made a grab for a share of the handout.

Luckily, there was a problem. Holtec does not have an operating license for Palisades. Nor has it ever operated a nuclear reactor so another company would need to be found to do that. The reactor was out of fuel. And of course there were all those technical and safety problems that would have to be addressed and, presumably, paid for.

Late last week, the US Department of Energy turned down Holtec’s request for funding from the Civil Nuclear Credit program, which would potentially have given the green light to Holtec to reopen Palisades.

Read MoreTime isn’t on their side

Why is the US government still pouring tax dollars into SMRs?

By Linda Pentz Gunter

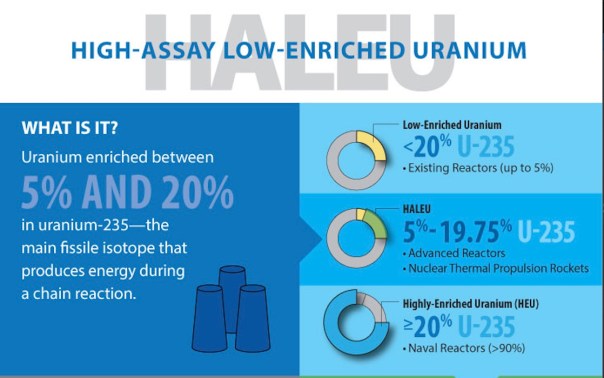

Among the myriad problems of the ever-promised-but-never-quite-here Small Modular Reactors (SMR)—aside from the fact that there is no economic rationale or established demand for ordering them — is access to the fuel most of the models would require.

With the exception of the NuScale reactor design, which is based on the traditional light water reactor, many of the remaining American SMRs on the drawing board would use High Assay Low Enriched Uranium (HALEU) fuel, something only Russia commercially manufactures currently. (The “low enriched” in the name is misleading as the uranium is actually enriched to close to 20% which borders on weapons-usable.)

On the one hand, the US and European Union countries appear to have no “energy security” concerns about continuing to import raw uranium and nuclear fuel from an increasingly hostile Russia already at war in Ukraine amid tightening fuel embargoes.

On the other hand, the need to import HALEU from Russia has suddenly prompted an attack of conscience in at least one quarter.

“We didn’t have a fuel problem until a few months ago,” Jeff Navin, director of external affairs of the Bill Gates owned company, TerraPower, told Reuters. “After the invasion of Ukraine, we were not comfortable doing business with Russia.”

Before the invasion, Russia was in the habit of exiling, imprisoning, poisoning and assassinating its detractors, including Russian journalists. But that, apparently, was no deterrent to Terrapower and others.

Read More Beyond Nuclear International

Beyond Nuclear International