Linda Walker’s healing touch

Her Chernobyl Children’s Project UK helps the young seek respite and joy

By Linda Pentz Gunter

When a deadly nuclear power plant accident spreads radiation across the world, you can’t take it back. That contamination, from the 1986 Chernobyl disaster in the Ukraine, hit neighboring Belarus the hardest. Not only those living there at the time, but children born since, have suffered the health effects of exposure to long-lasting radioactive fallout.

The long-term solution, of course, is to rid the world of nuclear power plants, ensuring that no one need suffer from their deadly poison again. But in the short-term, solutions are also needed to help those suffering today. That is where Linda Walker stepped in.

Linda started her charity Chernobyl Children’s Project UK in 1995, inspired by Chernobyl Children International, founded in 1991 in Ireland by Adi Roche. Linda quickly realized that in addition to bringing children from Chernobyl-affected areas to the UK for so-called “radiation vacations,” something more was needed. She decided that her group needed to be active on the ground as well, in particular in Belarus. She has been traveling to the country on a frequent basis ever since.

Alfred Sepepe keeps hope alive

South African besieged with sickness won’t give up fight for worker compensation

By Linda Pentz Gunter

Alfred Manyanyata Sepepe is 66 now. And he is back in the hospital. This time it is lung cancer. Last time it was testicular cancer. On April 9 Sepepe asked to be discharged from the hospital so that he could again go to the Public Protector’s office, a place he has been hundreds of times before. For, while Sepepe has been struggling to stay alive himself for more than 18 years, he has dedicated that time to keeping something else alive — a compensation bid for the former workers at South Africa’s Pelindaba nuclear research center.

Today, the work at Pelindaba focuses on the production of medical isotopes. But Pelindaba was also the site where South Africa secretly developed its nuclear weapons, until the country renounced nuclear weapons and began dismantling its bombs in 1989. At the time it had six completed atomic bombs and one still under construction. The work was done under the guise of “peaceful” nuclear energy development.

Alfred Manyanyata Sepepe

Sepepe, who came from the nearby town of Atteridgeville that supplied much of the Pelindaba workforce, began working in the nuclear complex in 1989, first at the neighboring Advena nuclear laboratory and then at Pelindaba, managed by the South African Nuclear Energy Corporation (NECSA.) He worked as a cleaner, operated machinery and poured chemicals. And he noticed, almost immediately, that there was no protective gear offered to the Pelindaba workers.

“I asked my foreman why we had to work with chemicals,” Sepepe recalled. “And he chased me out.”

The View from the Ferris Wheel

If we treat each other like expendable dots, can we hope to preserve our humanity?

By Linda Pentz Gunter

The missile attacks this weekend on Syria — by US, French and British forces — are another reminder of just how impersonal war has become. Targets are reportedly hit. But what of the suffering on the ground which, in Syria, is already considerable?

This long-distance and impersonal style of war-making is nothing new of course. We cannot forget the aerial bombing campaigns during World War II and beyond, when terrorized civilians ceased to be human beings but were simply “collateral damage.” Today, we simply have bigger and faster weapons with even greater destructive power.

That’s why I appreciated the analogy former Swiss politician, Moritz Leuenberger, made during last September’s Human Rights, Future Generations and Crimes in the Nuclear Age conference in Basel, Switzerland.

Lamenting the loss of human compassion, he reminded us of the famous scene at the top of the Vienna ferris wheel in The Third Man, when Harry Lime, played by Orson Welles, looks down at the children playing below and asks his old friend Holly Martins (Joseph Cotton): “Would you really feel any pity if one of those dots stopped moving forever?”

“This is how we lose compassion,” Leuenberger said. “The further away from people that we are.”

In Leuenberger’s case, his presentation was specifically about the victims of the nuclear chain — the fact that our parasitic behavior today will leave an unending debt of ill health and radiation exposures for generations to come.

Risking shoot-to-kill to stop the killing machine

The Nuns, the Priests and the Bombs is a new film about old style non-violence

By Linda Pentz Gunter

Would you be willing to put your life on the line to make a moral statement about the iniquity of nuclear weapons? I am willing to bet that most of us, however strongly we feel about the need to abolish the Bomb, would not walk peacefully into a shoot-to-kill zone at a nuclear weapons complex just to make a point.

But when it is a point of conscience, of morality, and of faith, that is exactly what members of the Plowshares movement will do. And have done. For decades.

Seven of them just did it again, as they always say they will. Arrest them, try them, convict them and jail them, but their determination and moral conviction will not be eroded. They are repeat offenders. But they do not come to offend.

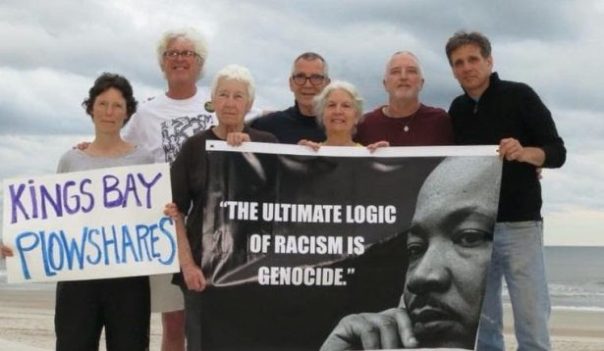

So on April 4, 2018, the anniversary of the assassination of peacemaking leader, Dr. Martin Luther King, the self-styled Kings Bay Plowshares entered the King’s Bay Naval Base in St. Mary’s, Georgia, the largest submarine base in the world. As had their colleagues before them, they carried banners, statements, hammers and blood. They were arrested, then denied bond during a preliminary hearing on April 6.

The seven members of the Kings Bay Plowshares, who entered the Georgia naval base on April 4 to protest nuclear weapons, white supremacy and racism. (WNV/Kings Bay Plowshares)

Nuclear companies are just happy to be in there somewhere

And they’ll gouge the ratepayers to get there

By Linda Pentz Gunter

That teeth-jangling noise you can hear are the fingernails of nuclear power corporations scraping across window ledges in a last, desperate attempt to cling on. It’s a lost cause. Nuclear power is falling to its none too premature death. It just won’t go quietly.

Instead, like Steve Martin’s unforgettable character in The Jerk, the mantra for nuclear corporations has become “I’d just be happy to be in there somewhere.”

The only chance for nuclear energy companies to stay relevant, and even alive, is to squeeze ratepayers. It’s their last, selfish recourse to prop up aging, failing and financially free falling nuclear power plants that should have closed years ago (and in fact should never have been built in the first place.)

Consequently, even as we tentatively celebrated First Energy’s just announced early closures of its four nuclear reactors — Davis-Besse (OH), Perry (OH) and two at Beaver Valley (PA, pictured at top) — we knew that something more devious was afoot.

Naoto Kan gets a closeup view of nuclear France

The former Japanese PM visits Flamanville and La Hague, and draws 400 locals to an inspiring evening event in Normandy, France

By Linda Pentz Gunter

Most of the time you don’t see former leaders of major world powers trudging along windy clifftops as they listen to anti-nuclear activists hold forth. That is why I find the odyssey of former Japanese Prime Minister, Naoto Kan, ever more extraordinary. For a handful of years now he has been traveling around the world speaking out in favor of an end to the use of nuclear power. And he has been talking to us.

Naoto Kan visits a windswept Normandy beach from which you can see the Flamanville nuclear site as well as the La Hague reprocessing facility.

Kan of course was the Prime Minister in power at the time of the Fukushima nuclear disaster which struck on March 11, 2011. For all the mistakes and naiveté swirling at the time, Kan made one monumentally important decision. He picked up the phone and countermanded Tepco’s decision to pull its workforce out of the stricken Fukushim-Daiichi nuclear site.

That saved countless lives and likely the entire country. Untended, the reactors would have melted down and released a radioactive inventory that would have forced the abandonment of the neighboring Fukushima-Daiini nuclear plant. That in turn would have melted and the resulting cascading accident could have led to the evacuation of Tokyo. As Kan says in every speech, losing Tokyo would have been the end of Japan.

Beyond Nuclear International

Beyond Nuclear International