Nuclear-Free Forum in Japan calls for worldwide end to nuclear power

Voices of Fukushima power plant explosion victims strengthen call to ban nuclear energy

By Rachel Farmer, Anglican Communion News

Japanese parish priests shared stories of suffering from victims of the Fukushima nuclear disaster at a May 2019 International Forum for a Nuclear-Free World held in Sendai, Japan. A joint statement from the forum, issued in July 2019, strengthens the call for a worldwide ban on nuclear energy and encourage churches to join in the campaign.

The statement – Affirming the Preciousness of Life, in Order that Life may be Lived – For a World Free of Nuclear Power – noted that “We believe that it is highly important that this issue of nuclear power generation be considered from the perspective of the dignity of life.” The statement went on to point out the dangers of continued radioactive waste production and the connection between nuclear power and nuclear weapons — “two sides of a single coin.” It recommended that “No longer should we continue as a society with the economic priority of reliance upon nuclear power generation.”

The forum, organised by the Nippon Sei Ko Kai (NSKK) – the Anglican Communion in Japan – follows the NSKKs General Synod resolution in 2012 calling for an end to nuclear power plants and activities to help the world go nuclear free.

The disaster in 2011 followed a massive earthquake and tsunami which caused a number of explosions in the town’s coastal nuclear power station and led to widespread radioactive contamination and serious health and environmental effects. The Chair of the forum’s organising committee, Kiyosumi Hasegawa, said: “We have yet to see an end to the damage done to the people and natural environment by the meltdown of TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. I do think this man-made disaster will haunt countless people for years to come. We still see numerous people who wish to go back to their hometowns but are unable to. We also have people who have given up on ever going home.”

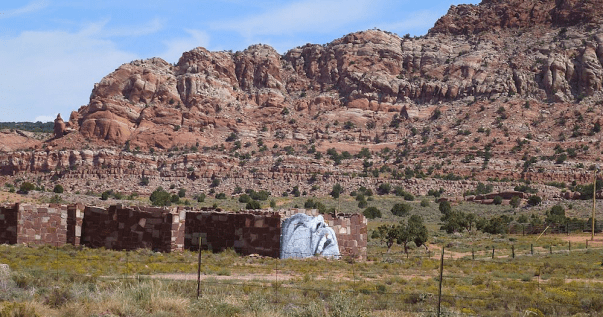

Photographic art in the painted desert

The dreaming doctor who is wide awake

By Linda Pentz Gunter

“The question I’m asked most frequently is how a black doctor in his 50s working on the Navajo reservation started doing street art on said reservation”, relates Chip Thomas on his website Jetsonorama — whose name itself begs yet another question (we’ll answer that one later in the story. Thomas is in his early 60s now).

Thomas has been asked this same question over and over the last few years, ever since his story caught fire in the (mainly) non-traditional media. Thomas is a medical doctor, but also a photographer who has applied that skill to wall art. Those two passions merged when he began treating Native American patients in 1987. His medical practice is at the Inscription House Health Clinic and he lives nearby.

Chip Thomas wall art in the desert. Photo by Chris English, licensed in the Creative Commons/WikiCommons.

As a doctor, early experiences traveling, especially in Africa, convinced Thomas of the need for universal health care in the US. That led him to the Navajo Nation. His first dabbling in street art in cities like New York were, Thomas says on his website, of the more traditional kind, “largely text based saying things like ‘Thank you Dr. King. I too am a dreamer’ or ‘Smash Apartheid’ and so on.”

But inspired by the work of Gordon Parks, Eugene Smith and others, he soon realized that images of every day people could be equally powerful. Through his work, he told New Mexico PBS, he can now share their stories “in a way that honors them.” He says that “through my art I am attempting to uplift the human spirit to make the world a better place. So yeh, I’m a dreamer, but I’m a dreamer who’s wide awake.”

Chernobyl radiation proves harmful to vital forest mammal

New study finds abundance and breeding in decline among exposed bank voles

By Linda Pentz Gunter

A team of scientists who studied a key forest mammal, the bank vole, living within 50 km of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, have concluded that the animal’s reproductive success and abundance is impaired by chronic exposure to even “low” levels of radiation in the area, and that no dose is too low to cause these effects.

The large-scale, replicated study, by Mappes et al., and published in April 2019, “tested the hypothesis that ecological mechanisms interact with ionizing radiation to affect natural populations in unexpected ways.” The team found that bank voles showed “linear decreases in breeding success with increasing ambient radiation levels with no threshold below which effects are not seen.”

The bank vole was chosen because “it is a common and abundant terrestrial vertebrate that inhabits Eurasian forest ecosystems, which makes it an attractive indicator species for the health of forest ecosystems that may have been injured by anthropogenic activities,” wrote the authors.

Young bank voles in the nest. Reproduction declines, the higher the exposure to radiation, in voles within 50km of Chernobyl. (Photo: Plantsurfer/WikiCommons)

Les radiations de Tchernobyl nocives pour la faune sauvage et les écosystèmes

Résultats d’une nouvelle étude :

Le nombre de campagnols des bois et leur capacité reproductrice sont en déclin.

Il n’y a pas de seuil de radiation sous lequel il n’y aurait pas d’effet sur les populations d’animaux

Linda Pentz Gunter

Une équipe de scientifiques qui ont étudié les campagnols des bois se trouvant à moins de 50 km de la centrale nucléaire de Tchernobyl a conclu que les capacités reproductrices de ces mammifères et par conséquent leur population souffrent d’une exposition chronique aux rayons présents dans la région et que ces effets s’observent même quand les doses sont infimes.

L’étude, menée à grande échelle et à plusieurs reprises par Mappes et al. et publiée en avril 2019, « a testé l’hypothèse selon laquelle les mécanismes écologiques interagissent avec les rayonnements ionisants pour affecter de manière inattendue les populations naturelles ». L’équipe a constaté que les campagnols des bois ont montré « des diminutions linéaires du taux de fertilité en fonction de niveaux ambiants croissants de radiation, sans seuil en dessous duquel des effets ne seraient pas observés ».

Le campagnol des bois a été choisi parce que « c’est un vertébré terrestre commun et abondant qui habite les écosystèmes forestiers eurasiens, ce qui en fait une espèce indicatrice intéressante pour la santé des écosystèmes forestiers qui peuvent avoir été déteriorés par des activités anthropiques », écrivent les auteurs.

De jeunes campagnols des bois dans le nid. Plus l’exposition au rayonnement est élevée, plus le taux de fertilité diminue chez les campagnols dans un rayon de 50 km autour de Tchernobyl. Photo : Plantsurfer/WikiCommons.

Lorsque le réacteur de Tchernobyl a explosé le 26 avril 1986, il a libéré des produits de fission en Ukraine, en Russie, en Biélorussie et ailleurs en Europe. Il s’agit notamment du strontium-90, du césium-137 et du plutonium-239, qui ont contaminé l’air, le sol et l’eau. Les retombées radioactives s’accumulent dans les plantes et les animaux, sources de subsistance de la faune. Au moins 90 études publiées par de nombreux membres de l’équipe Mappes ont mis en évidence de graves effets délétères de l’exposition aux rayonnements chez les animaux sauvages de Tchernobyl, en particulier les oiseaux, qui souffrent de cataractes, de tumeurs, d’un taux de spermatozoïdes réduit ou nul et d’une diminution de la taille du cerveau.

La nouvelle étude Mappes est importante parce qu’elle s’inscrit dans un corpus de travaux scientifiques qui réfutent l’idée selon laquelle, simplement parce qu’« il y a beaucoup d’animaux dans la zone de Tchernobyl », ils ne sont pas affectés par l’accident nucléaire. Ces études sur la « faune sauvage prospère » induisent le public en erreur en lui faisant croire que les animaux de la région profitent de l’absence d’humains et qu’ils ne souffrent pas des effets nocifs de leur exposition soutenue aux rayonnements provoqués par la catastrophe nucléaire.

Dans Mappes et al., les chercheurs ont donné des compléments nutritifs à certains groupes de campagnols afin d’écarter la pénurie alimentaire comme cause de la diminution du taux de fertilité et de la population. Mais ils n’ont observé que peu de différence entre les campagnols qui recevaient ces compléments et ceux qui trouvaient leur nourriture tout seuls.

« Les populations bénéficiant des compléments alimentaires n’ont augmenté que dans les zones de faible radiation » (1 μSv/h ou moins), mais ont diminué lorsque les niveaux de radiation étaient plus élevés. Les campagnols qui ne recevaient pas de compléments « ont eu tendance à diminuer linéairement avec l’augmentation des niveaux ambiants de radiation ». Des niveaux plus élevés de rayonnement réduisaient leur nombre, qu’ils aient reçu ou non des compléments alimentaires. « Ainsi, des compléments alimentaires ne peuvent atténuer les effets nocifs d’un environnement contaminé par des radionucléides que jusqu’à un certain point », ont conclu les chercheurs.

La probabilité qu’une femelle de campagnol des bois soit enceinte a diminué de manière significative avec l’augmentation du niveau de rayonnement ambiant. Photo : « Bank Vole » par clairespelling1, sous licence CC BY 2.0.

L’importance d’étudier la réponse des campagnols des bois à l’exposition de rayonnement dans la nature a été renforcée par des résultats récents montrant que, « les organismes vivants dans leur habitat naturel semblent être beaucoup plus sensibles aux effets délétères du rayonnement ionisant » que les animaux exposés et testés dans des conditions de laboratoire. Dans une méta-analyse de Garnier-Laplace et al. en 2013, qui s’est penchée sur « les effets des contaminants radioactifs dérivés de Tchernobyl sur 19 espèces de plantes et d’animaux vivants dans des conditions naturelles », le groupe de chercheurs a constaté que « les organismes sauvages étaient plus de huit fois plus sensibles aux effets négatifs du rayonnement que ces mêmes espèces placées dans des conditions de laboratoire ou de modélisation », écrivent Mappes et al.

L’équipe de recherche a trouvé des impacts significatifs sur la population de campagnols des bois de l’exposition de rayonnement provoquée par l’accident nucléaire de Tchernobyl. « La probabilité qu’une femelle de campagnol des bois soit enceinte a diminué de manière significative avec l’augmentation des niveaux ambiants de rayonnement, » dit l’étude. La taille des femelles n’a pas modifié ces phénomènes. Le nombre de campagnols des bois n’était pas non plus corrélé avec la probabilité de reproduction ou la taille de la portée.

Les saisons n’affectent pas non plus leur nombre. « Les populations estivales et hivernales de campagnols des bois ont diminué de manière significative avec l’augmentation du rayonnement ambiant », constate l’étude.

Les résultats de l’étude appuient fortement le modèle linéaire sans seuil, qui affirme qu’il n’y a pas de dose de rayonnement si faible qu’elle ne cause plus de dommages. Mappes a constaté que « des effets nocifs significatifs de rayonnement sur les populations de campagnol des bois peuvent être observés même à des niveaux très bas de radioactivité ambiante ».

Le campagnol des bois est également une source importante de nourriture pour des hiboux et d’autres animaux sauvages de forêt. Photo : « 049 » de Mike Doss est sous licence CC BY 2.0.

Comment les campagnols sont-ils exposés ? Comme l’étude l’explique, les effets biologiques sur les campagnols « pourraient être causés par l’exposition directe au rayonnement gamma du milieu environnant ou par l’exposition aux particules alpha et bêta accumulées dans les animaux à partir des aliments. Par exemple, les champignons, un composant essentiel du régime alimentaire des campagnols des bois, peuvent être une source énorme de radionucléides émetteurs alpha et bêta. »

Le nombre de campagnols des bois et leur survie ne sont pas seulement importants pour l’espèce elle-même. Les campagnols servent également de proie indispensable à d’autres mammifères et oiseaux, y compris les rapaces comme les hiboux et les buses, les belettes, les renards et autres mammifères prédateurs — c’est donc une espèce-clé. Par conséquent, une réduction artificielle de la population de campagnols des bois due aux impacts négatifs de l’exposition au rayonnement peut commencer à affecter d’autres animaux dans la chaîne alimentaire. Ces animaux sont, bien sûr, probablement aussi affectés par l’exposition aux rayonnements, comme les nombreuses études antérieures l’ont indiqué.

Les conclusions de l’étude devraient être un avertissement fort à ceux qui sont prêts à minimiser ou à rejeter les dommages causés non seulement à la faune sauvage, mais aussi aux humains qui vivent dans des zones encore affectées par des niveaux inacceptables de contamination radioactive, ou qui sont obligés d’y retourner comme c’est le cas à Fukushima.

« Ces résultats suggèrent que les populations de rongeurs et, par conséquent, des écosystèmes entiers ont vraisemblablement été affectés sur environ 200 000 km2 en Europe orientale, septentrionale et même centrale, où les contaminants radioactifs provenant de la catastrophe de Tchernobyl sont encore mesurables dans une grande diversité d’espèces différentes et s’accumulent dans la chaîne alimentaire », selon l’étude Mappes. Ceci a déjà été observé dans des études sur les sangliers en Allemagne et les rennes en Finlande et en Suède, qui sont toujours trop radioactifs pour être consommés.

Comme l’ont conclu les chercheurs, « les études expérimentales présentées ici fournissent des preuves irréfutables que même de très faibles doses (0,1 μSv/h ou moins) peuvent entraîner des conséquences importantes pour les individus, les populations et même vraisemblablement des écosystèmes entiers ».

___

Read the full study: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332369605_Ecological_mechanisms_can_modify_radiation_effects_in_a_key_forest_mammal_of_Chernobyl

And watch a new podcast about Dr. Timothy Mousseau’s more than 50 trips to study animals living around Chernobyl: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/biologist-timothy-mousseau-cant-stop-going-back-to/id1370092284

Traduction : Fin du nucléaire asbl (www.findunucleaire.be).

La traduction est disponible sur le site de Fin du nucléaire asbl en PDF, pour imprimer.

____

Autres articles similaires sur le site de Fin du nucléaire asbl :

- À Tchernobyl et Fukushima, la radioactivité a gravement impacté la faune sauvage. Timothy A. Mousseau,professeur de biologie à l’Université de Caroline du Sud (2016).

- Vers l’extinction des espèces animales à Tchernobyl. Un exposé de Michel Fernexlors du colloque Radioactivité et Santé organisé par le Grappele2 mars 2012.

Cliquer sur les liens ci-dessous ou aller sur le site www.findunucleaire.be, page Documents, section Articles. Ensuitecliquer sur « ce répertoire » et le dossier « –articles ».

Five myths about the Chernobyl disaster

No, wildlife isn’t thriving in the zone around the nuclear plant

By Kate Brown

More than three decades ago, a reactor at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in the Ukrainian republic of the Soviet Union exploded. A fierce fire burned for the following two weeks, sending columns of radioactive gases and particles across the European landscape and beyond. The accident is an enduring subject of fascination – HBO recently adapted the event into a hit miniseries, and the site is a popular tourist destination – leading to conjecture and misconception.

MYTH NO. 1

It resulted in only a few fatalities and casualties

For the past three decades, official reports of casualties and deaths from the Chernobyl accident have been surprisingly modest. Two people died immediately. Twenty-nine died in hospitals, and much later, 15 children died of Chernobyl-induced thyroid cancers.

These numbers have been repeated in recent articles in Newsweek and LiveScience.

Estimates of Chernobyl’s future health effects are also low: In 2006, researchers at the U.N. International Agency for Research on Cancer estimated that Chernobyl-induced cancers by 2065 will total 41,000, compared with several hundred million other cancers from other causes. Forbes even claimed that “only the fear of radiation killed anyone outside the immediate area,” by elevating rates of alcoholism and depression.

Photos of Chernobyl liquidators displayed at a 2010 Independent WHO protest in Paris, France. (WikiCommons)

The actual numbers may be far higher. Unfortunately, Belarus (where 70 percent of Chernobyl fallout landed), Russia and Ukraine have no public tallies of Chernobyl-related fatalities to update the count. But other state data gives us a rough sense of the number of people affected by the disaster over time.

In January 2016, for example, the Ukrainian government said 1,961,904 people in Ukraine were officially victims of the Chernobyl disaster. Ukraine also pays compensation to 35,000 people whose spouses died from Chernobyl-related health problems. These figures do not count Russia or Belarus, where estimates of cancers and fatalities are in the hundreds of thousands.

Πέντε μύθοι για την καταστροφή στο Τσερνομπιλ

Μετάφραση από τη Μαρία Σωτηροπούλου

της Kate Brown

MYΘΟΣ NO. 1

Φωτογραφίες των εκκαθαριστών που επιδείχθηκαν το 2010 σε ανεξάρτητη διαδήλωση WHO στο Παρίσι, France. (WikiCommons)

MYΘΟΣ NO. 2

Ουαλλοί κτηνοτρόφοι και τα κοπάδια τους επηρεάστηκαν από τη ραδιενέργεια του Chernobyl επί δεκαετίες. (Photo: Rachel Davies, 2011, WikiCommons)

MYΘΟΣ NO. 3

Great tits κοντά στο Chernobyl — στ αριστερά φυσιολογικό, στα δεξιά με καρκίνο προσώπου.

MYΘΟΣ NO. 4

Οι αμερικανικές και σοβιετικές πυρηνικές δοκιμές απελευθέρωσαν 20 δισεκατομμύρια curies ραδιενεργού Ιωδίου από το 1945 μέχρι το 1962. (Photo: Castle Romeo, US Department of Energy)

MΥΘΟΣ NO. 5

Μέσα σε 36 ώρες από την πυρηνική καταστροφή , οι σοβιετικές αρχές μετακίνησαν 50,000 κατοίκους της πόλης Pripyat. (Photo: Jose Franganillo/Creative Commons)

Beyond Nuclear International

Beyond Nuclear International